The Evolution of Alum Rock Park: 1872-2022

The City Reservation

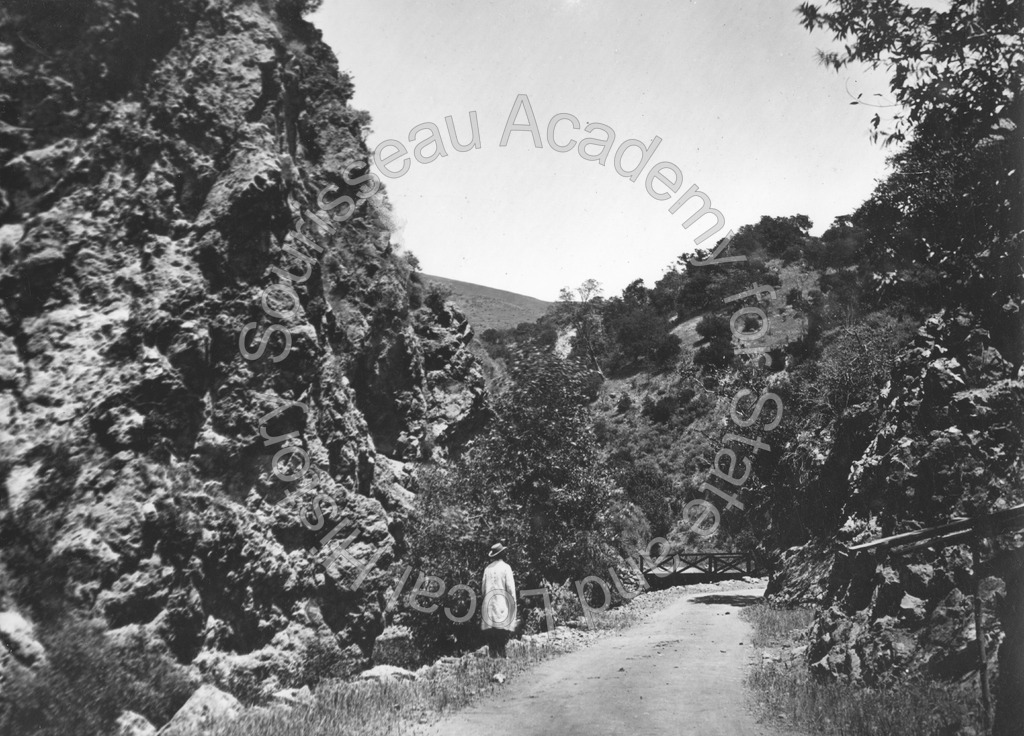

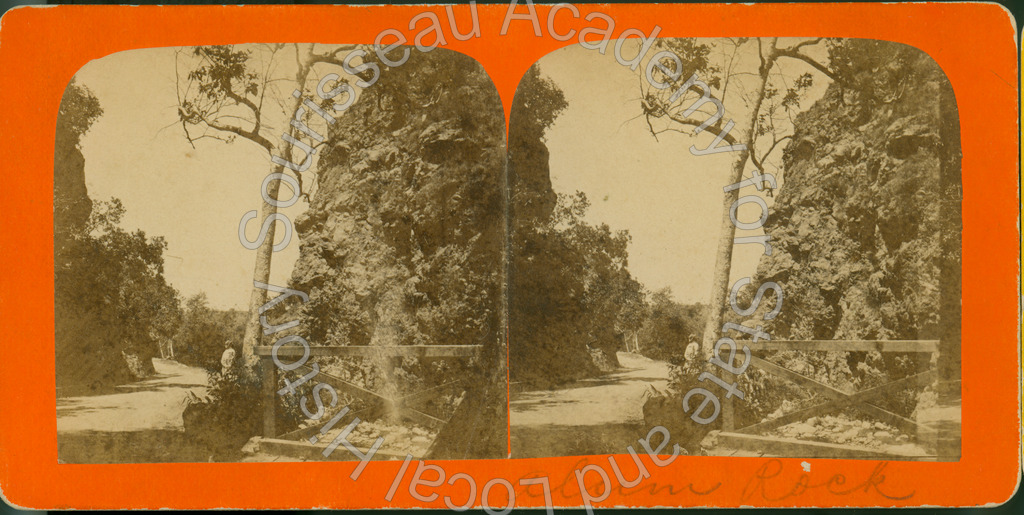

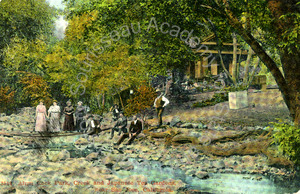

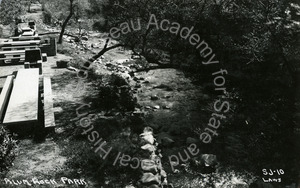

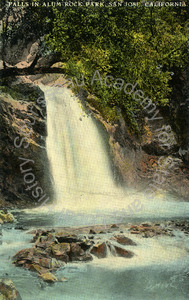

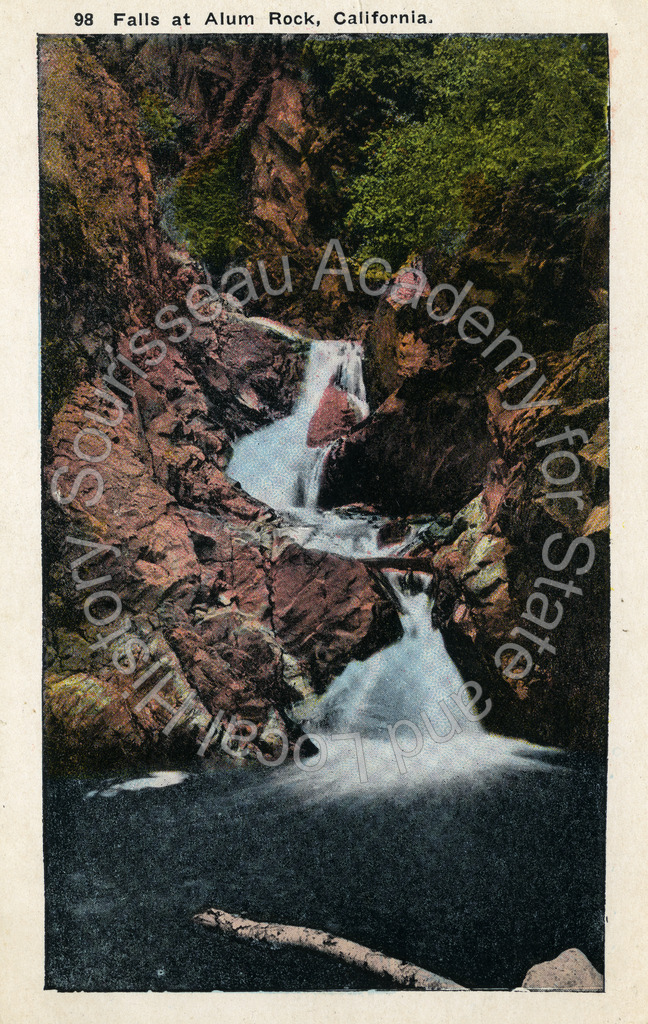

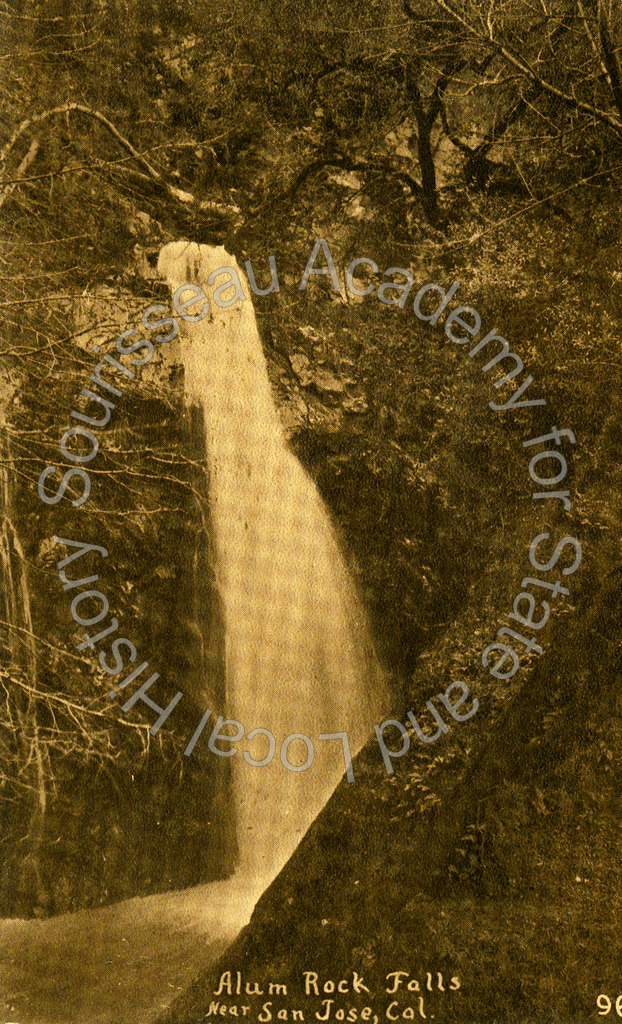

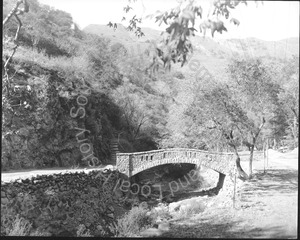

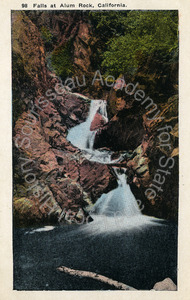

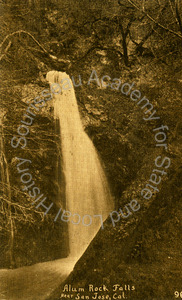

Along the bottom of a canyon in the foothills of the Diablo Range on the eastern outskirts of the city of San José flows a stream known historically as “Shistuk” by the local indigenous Tamien People. The first maps of the area note the stream’s name as “Arroyo Aguaje” but known as “Penitencia Creek” by the early 20th century residents of San José, the creek and its mineral springs became the foundation for a health resort built by private landowners in the 1850s and 1860s on the floor of the canyon.

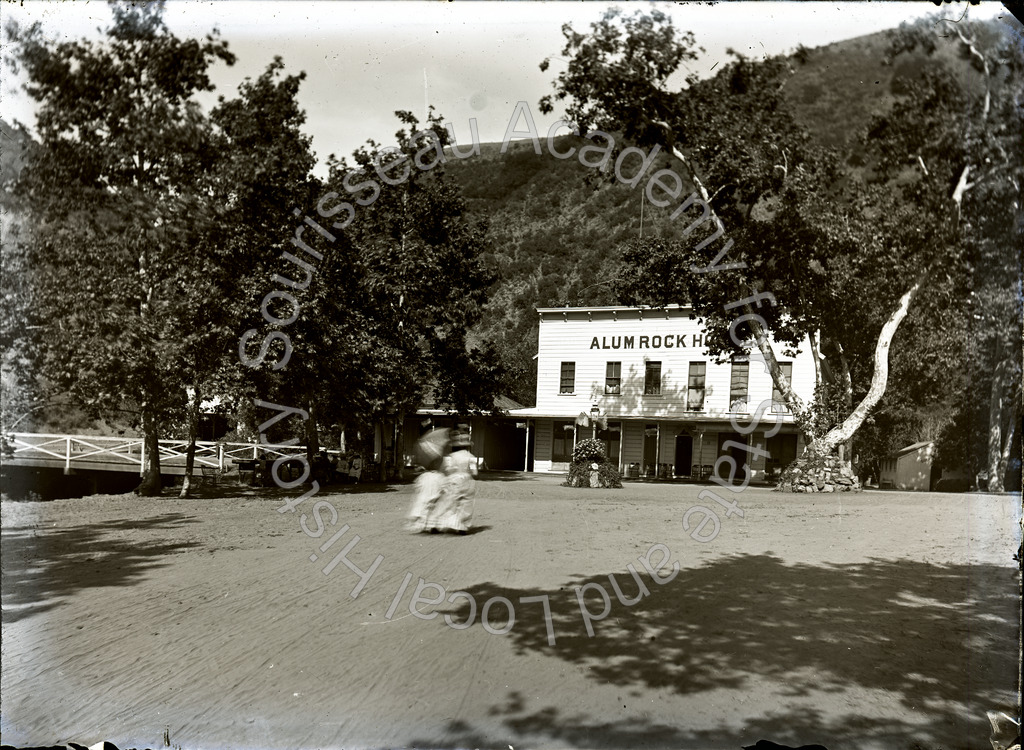

Early Santa Clara settler John M. Ogan had purchased land outside the canyon by 1853 and began calling the area “Alum Rock.” Although alum is not actually present in the large rock outcropping in the canyon, the canyon and surrounding area have been known by that name ever since. Ogan left the area a few years later and a settler named Woolsey Shaw then laid claim to much of the land that would become Alum Rock Park. Knowing that the mineral springs in the canyon could be an attraction to local residents, Shaw immediately built a hotel and bathhouse near the creek and some of its more accessible springs. He advertised the new “health resort” with the intent to attract nearby residents interested in the therapeutic benefits of soaking in the mineral and hot springs.

Within a few of years of Shaw building and developing the health resort inside the canyon, however, the city of San José accused Shaw of squatting on city property. The city claimed that the land Shaw developed was actually part of San José's original Spanish land grant and was known by the city as “The Reservation.” Shaw argued that because the area had long been left vacant and unused by the city that it was available for enterprising settlers such as himself to develop and use. This disagreement was the beginning of a long court battle during the course of which Shaw sold the health resort and some of the land to landowner Joseph O. Stratton. An 1866 court-ordered survey determined that the city was the rightful owner of the land, and Shaw and Stratton were forced to turn over ownership of the land, buildings, and resources to the city of San José.

Next: Establishing a Park

Establishing a Park

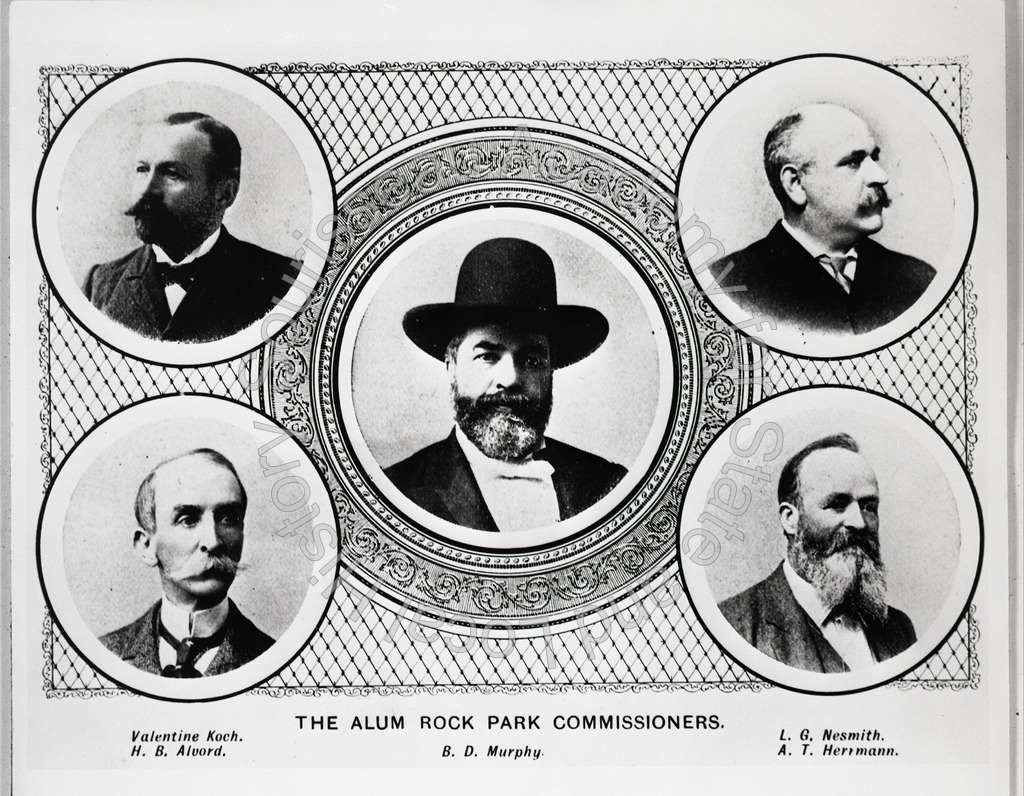

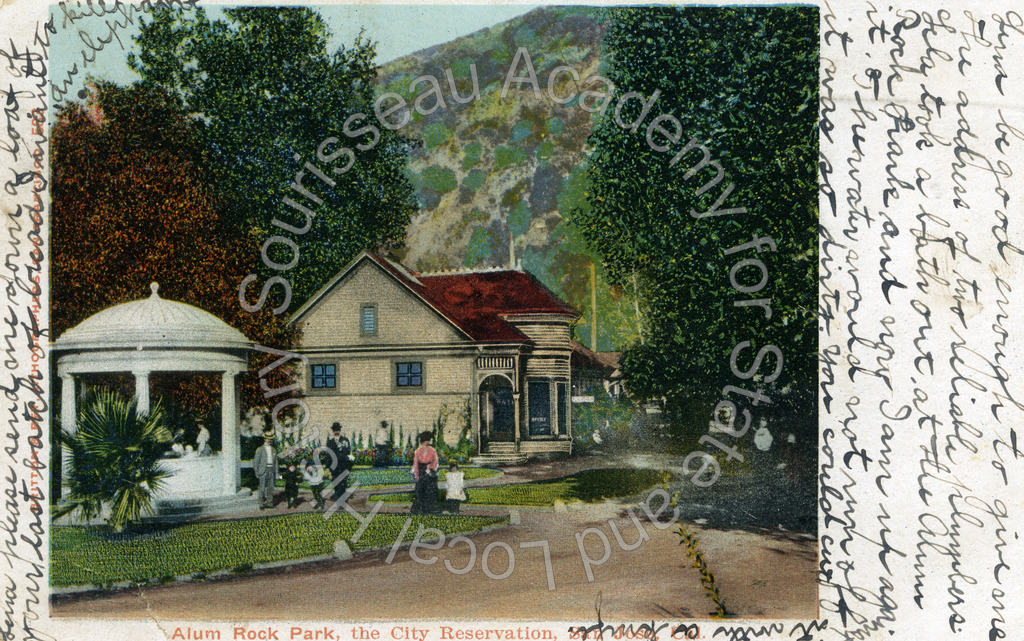

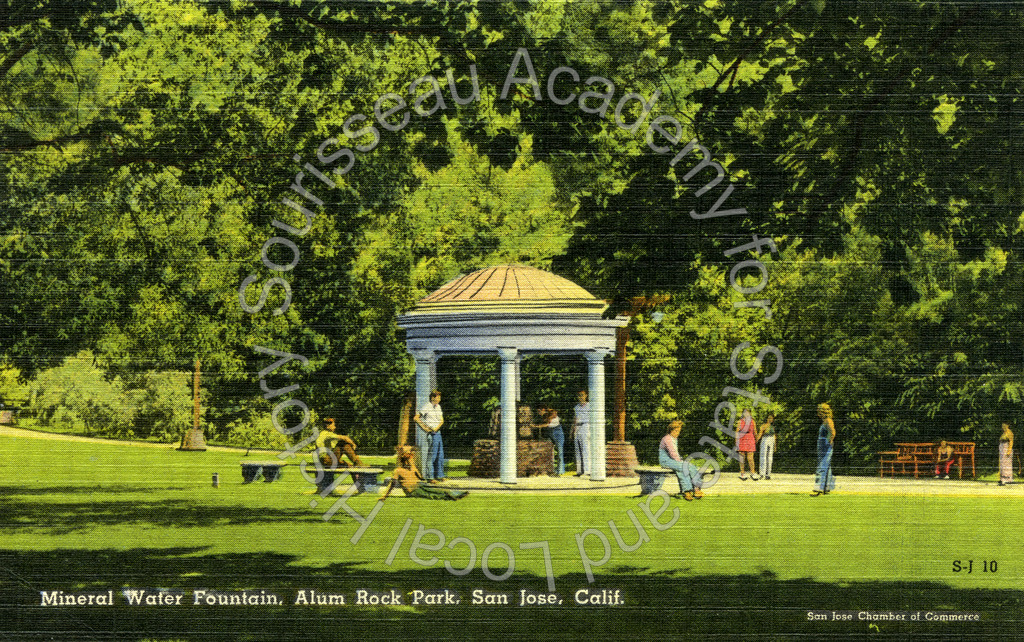

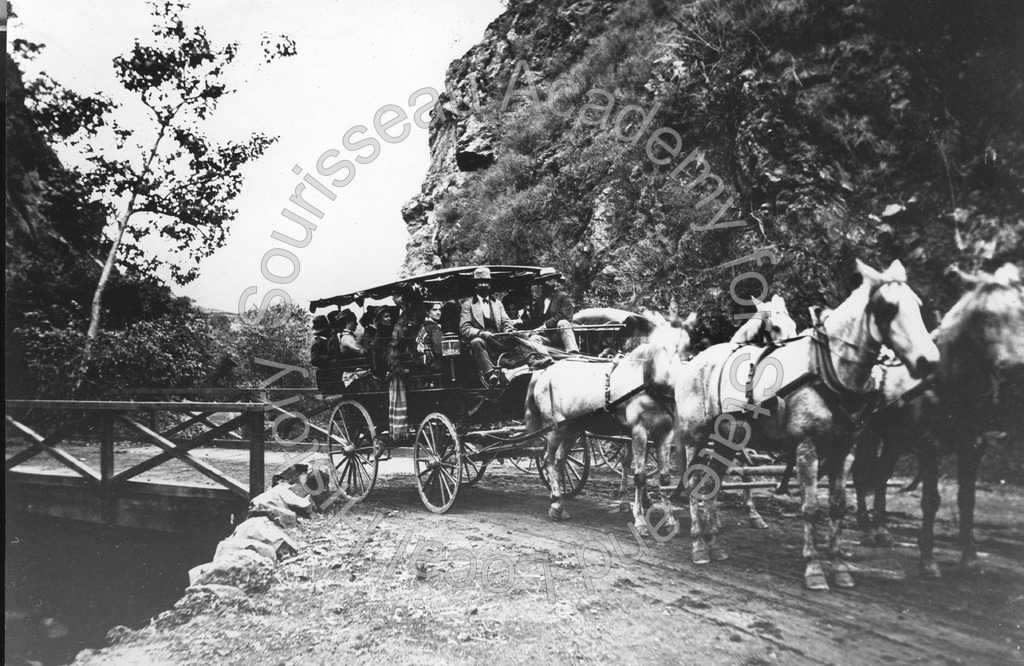

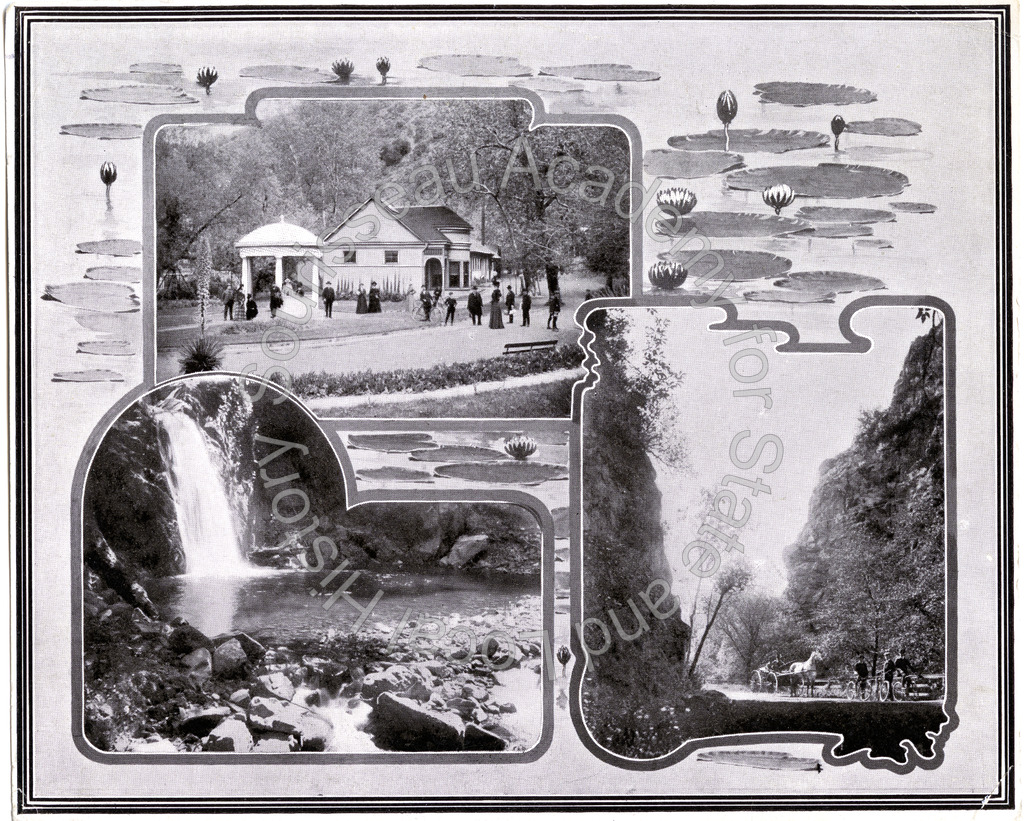

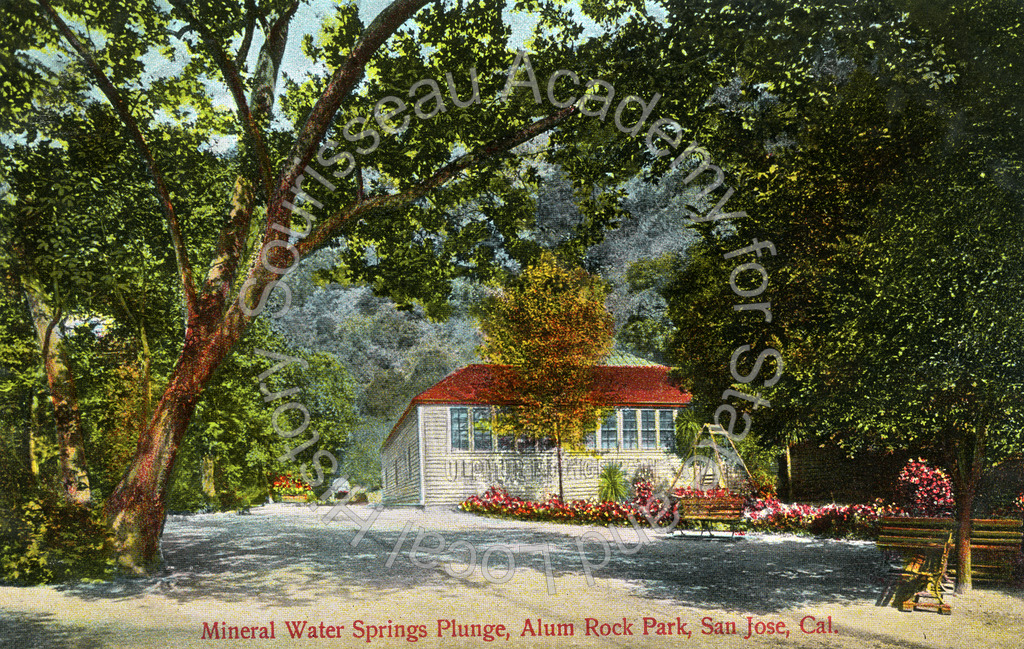

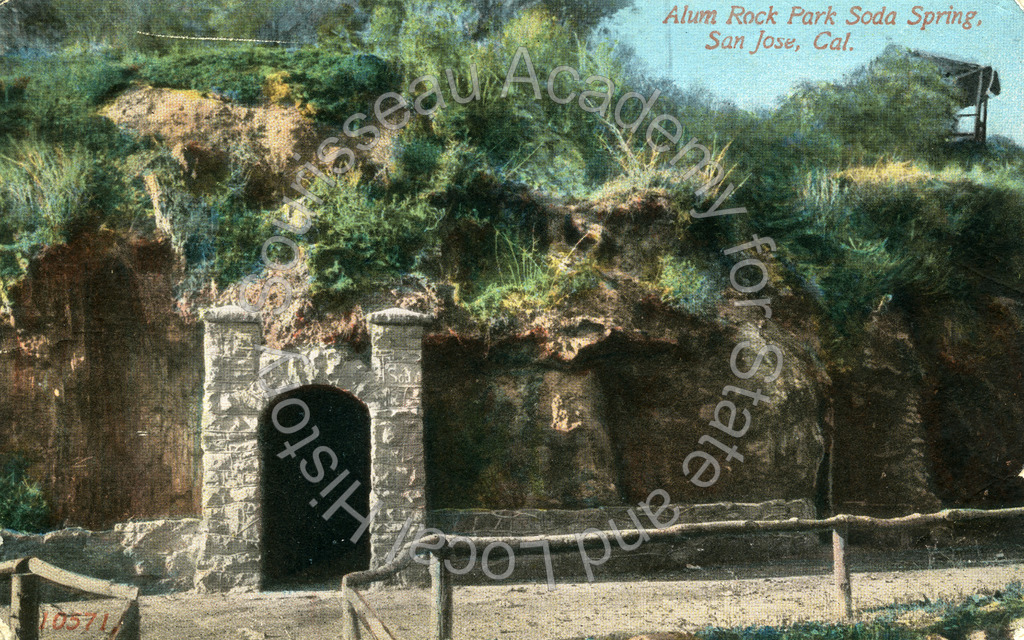

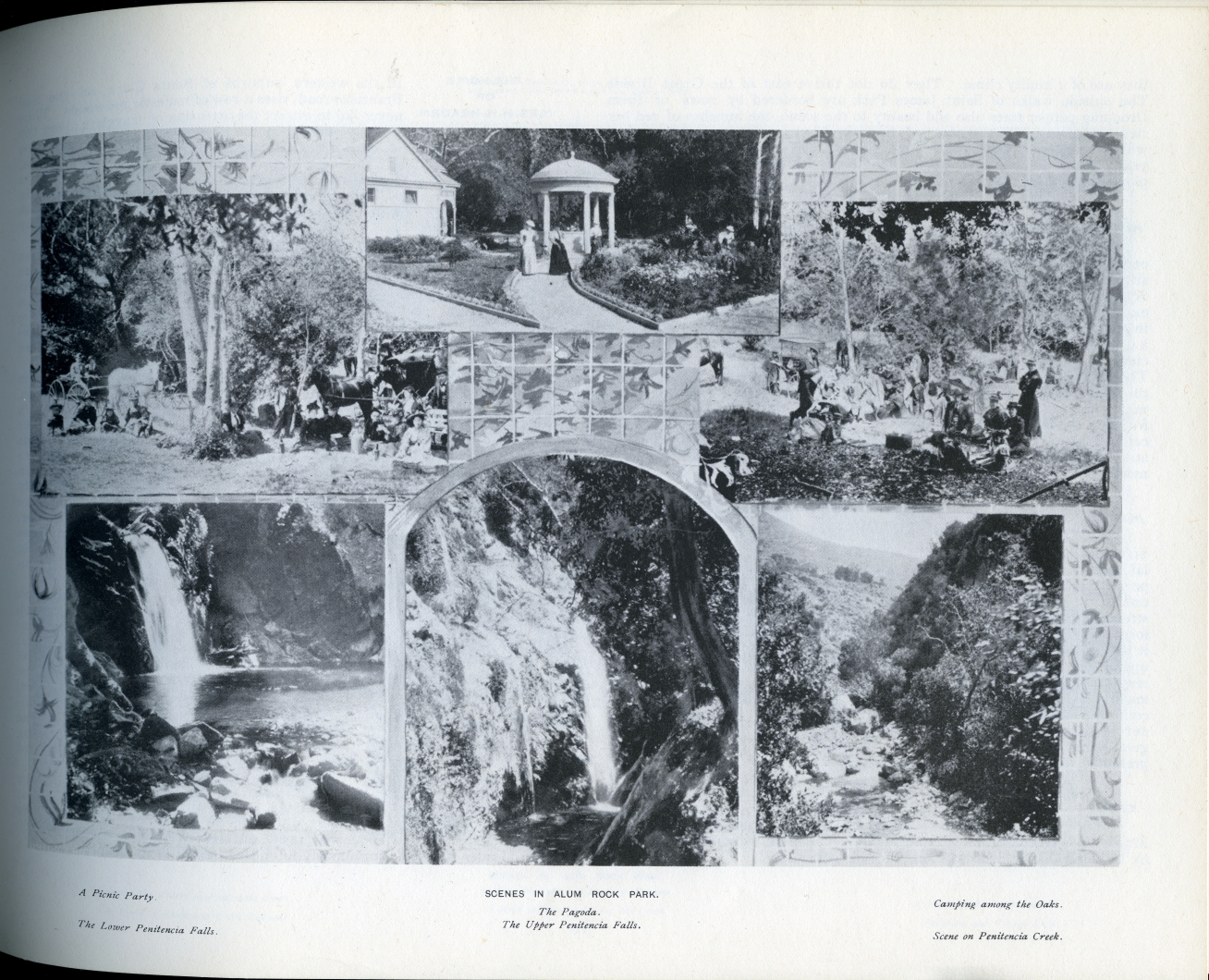

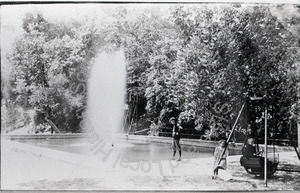

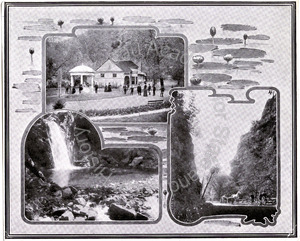

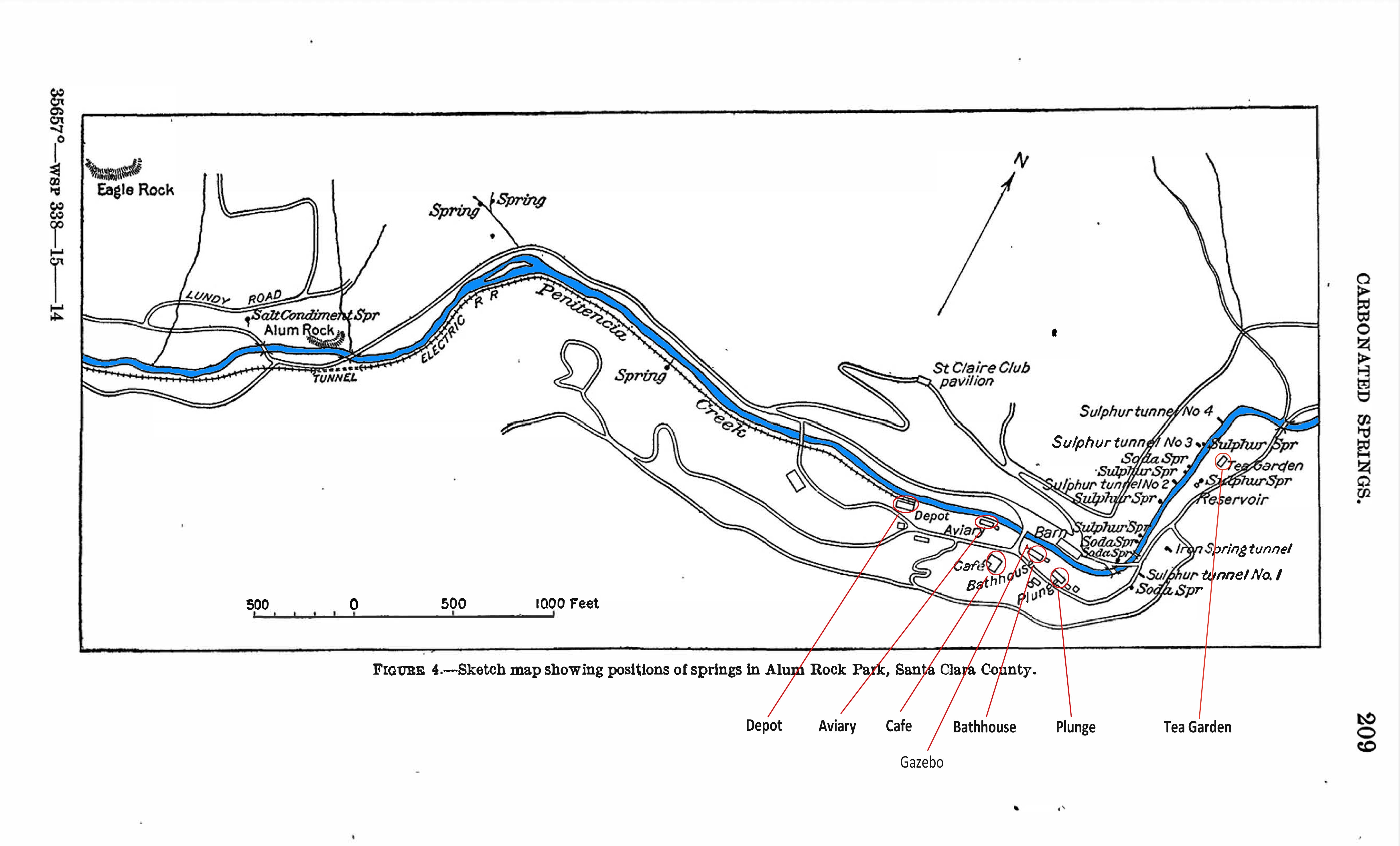

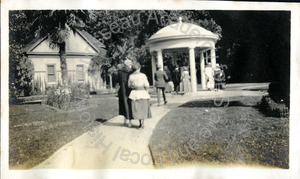

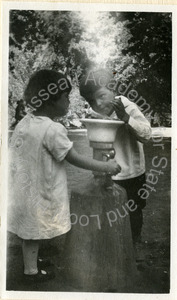

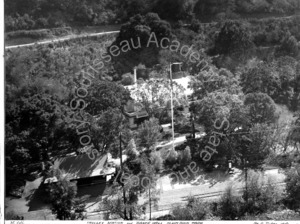

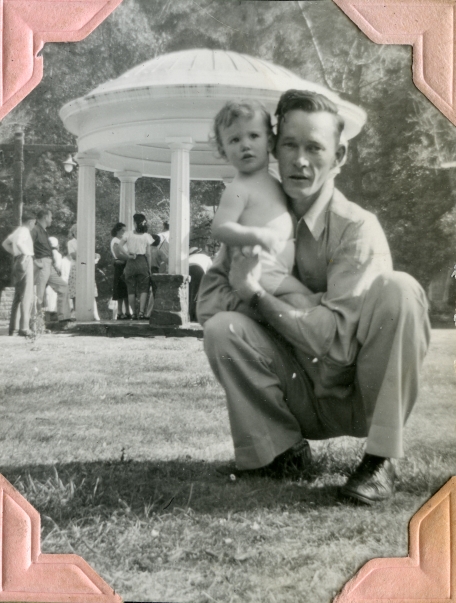

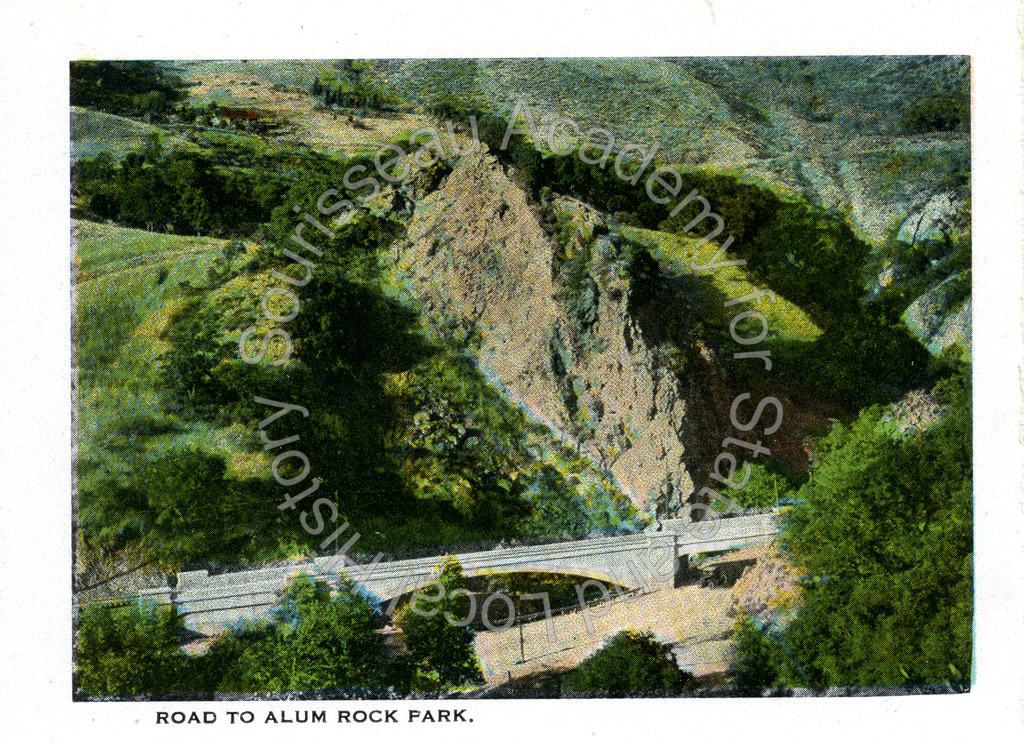

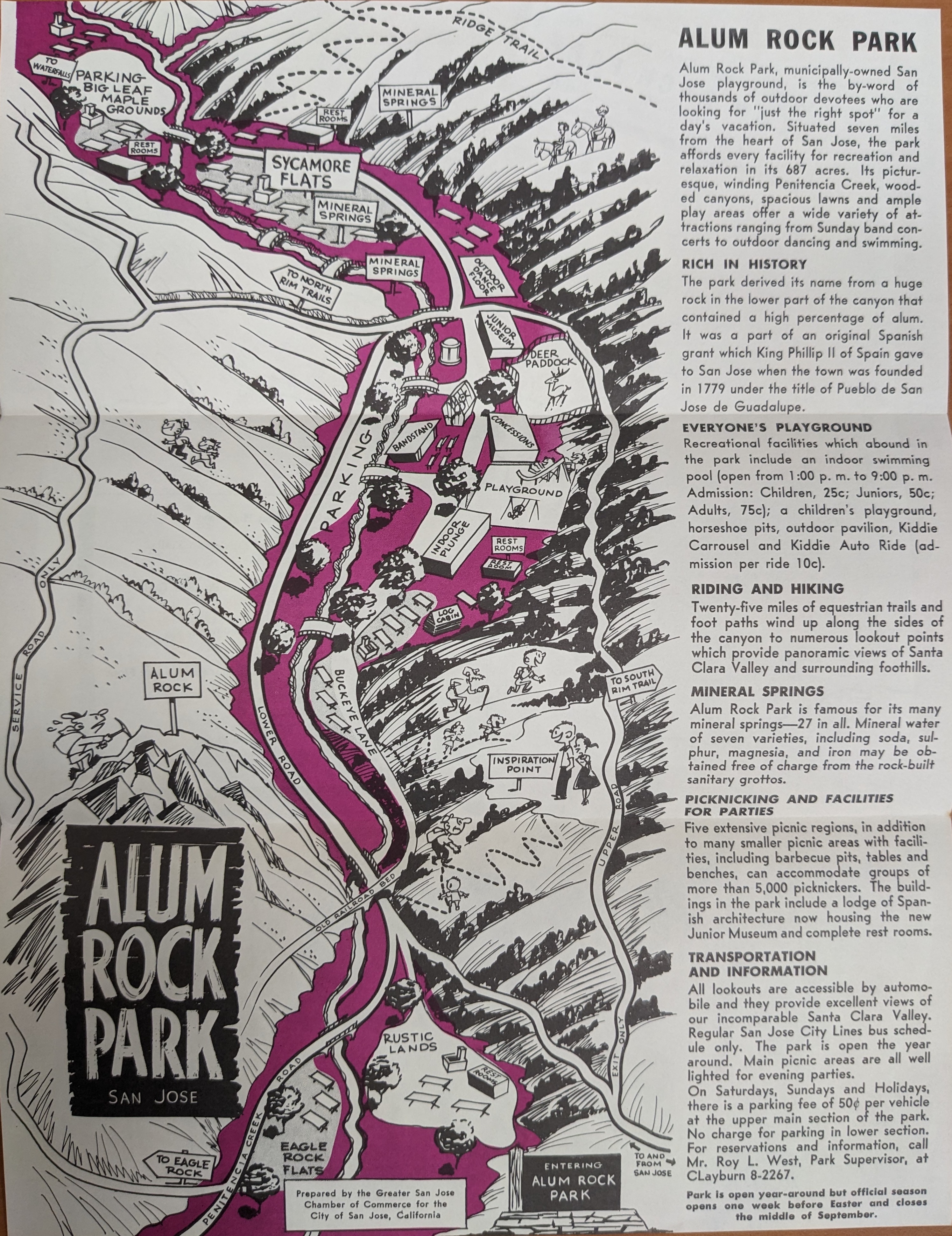

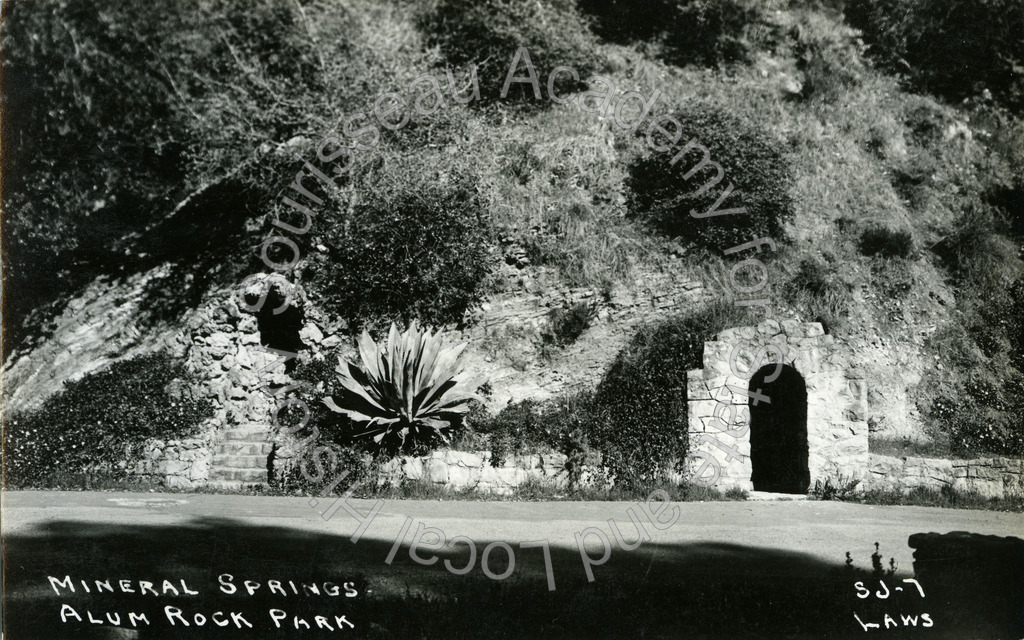

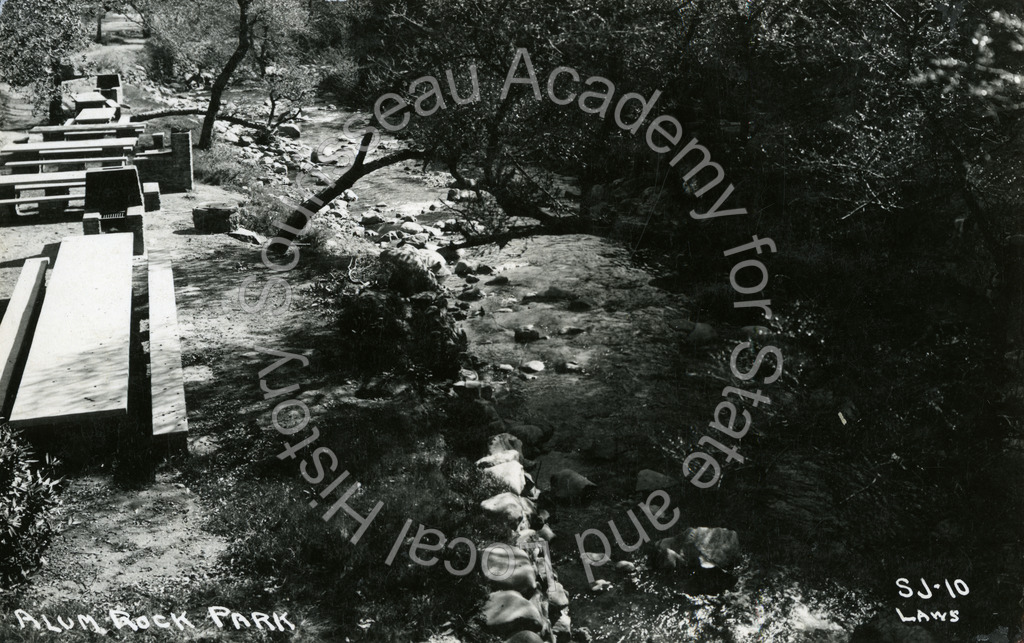

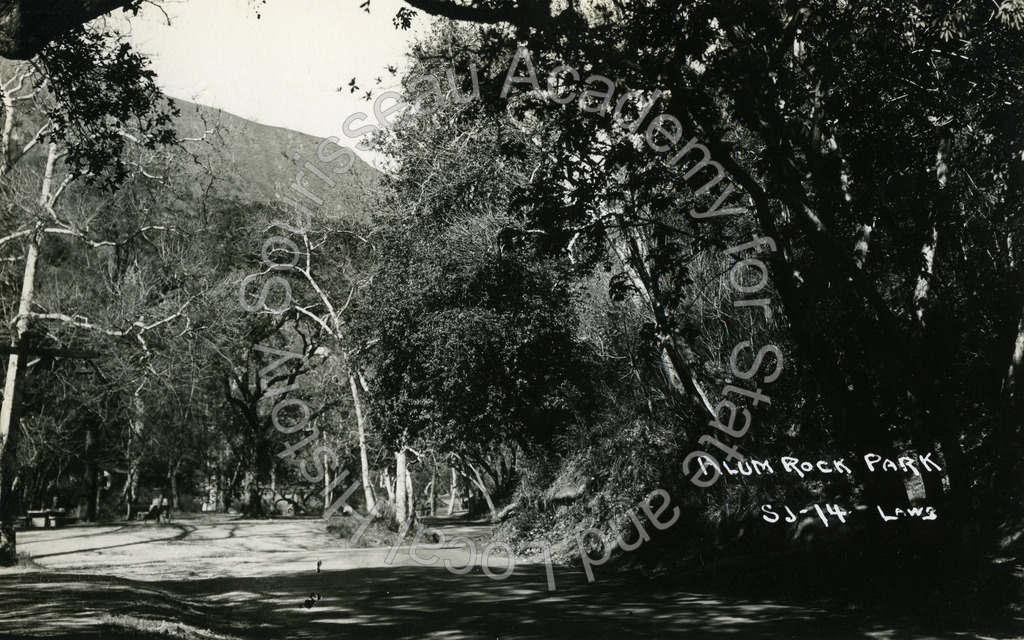

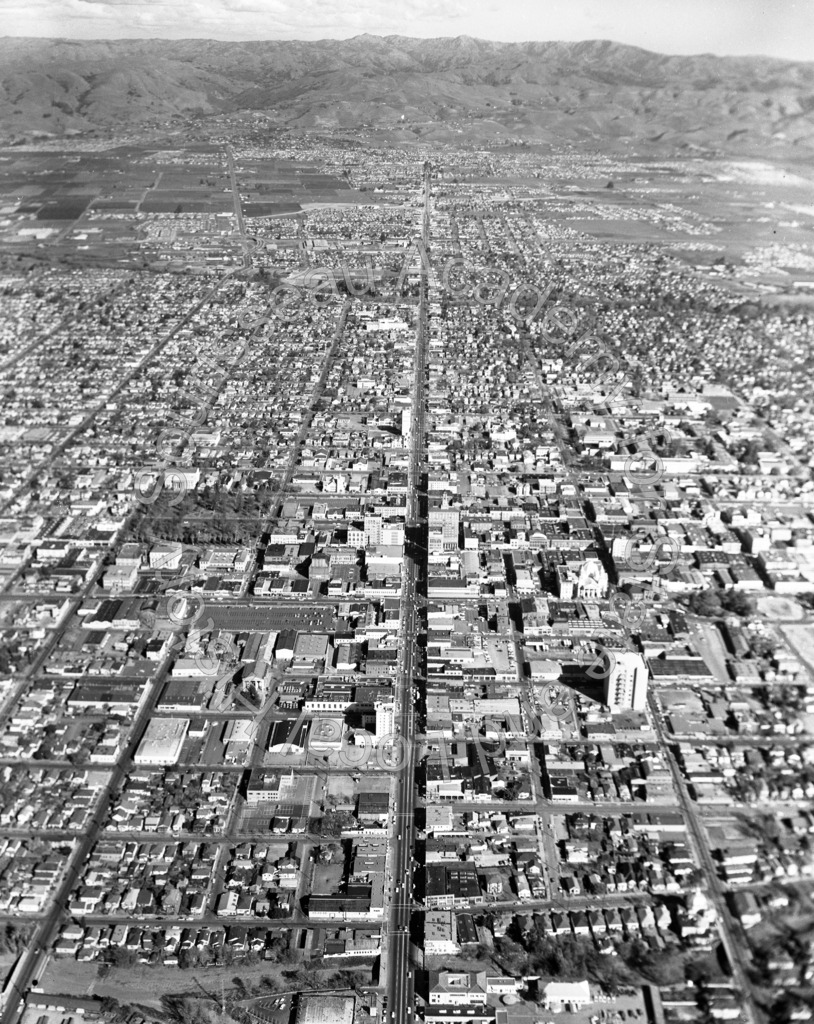

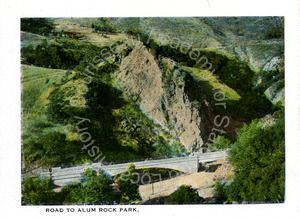

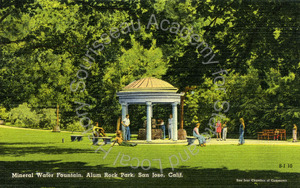

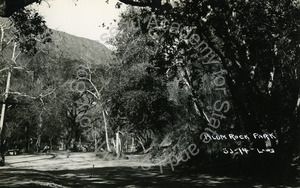

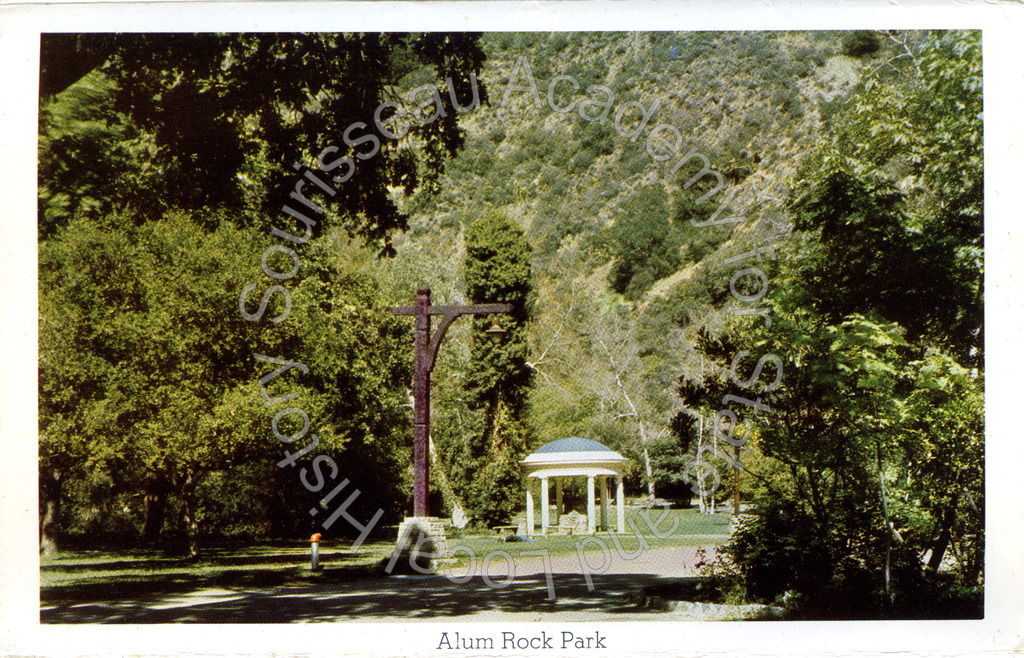

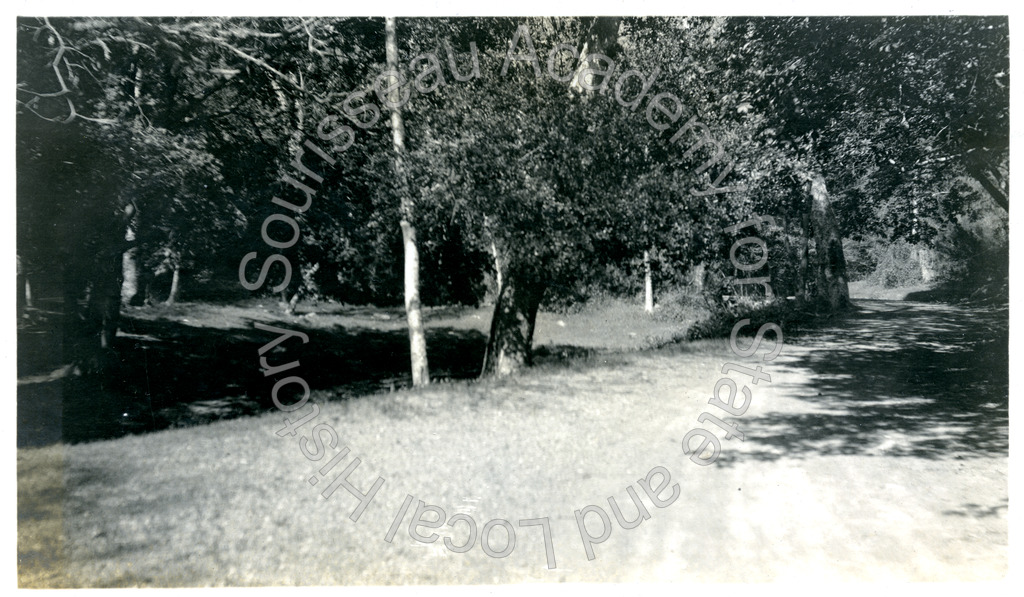

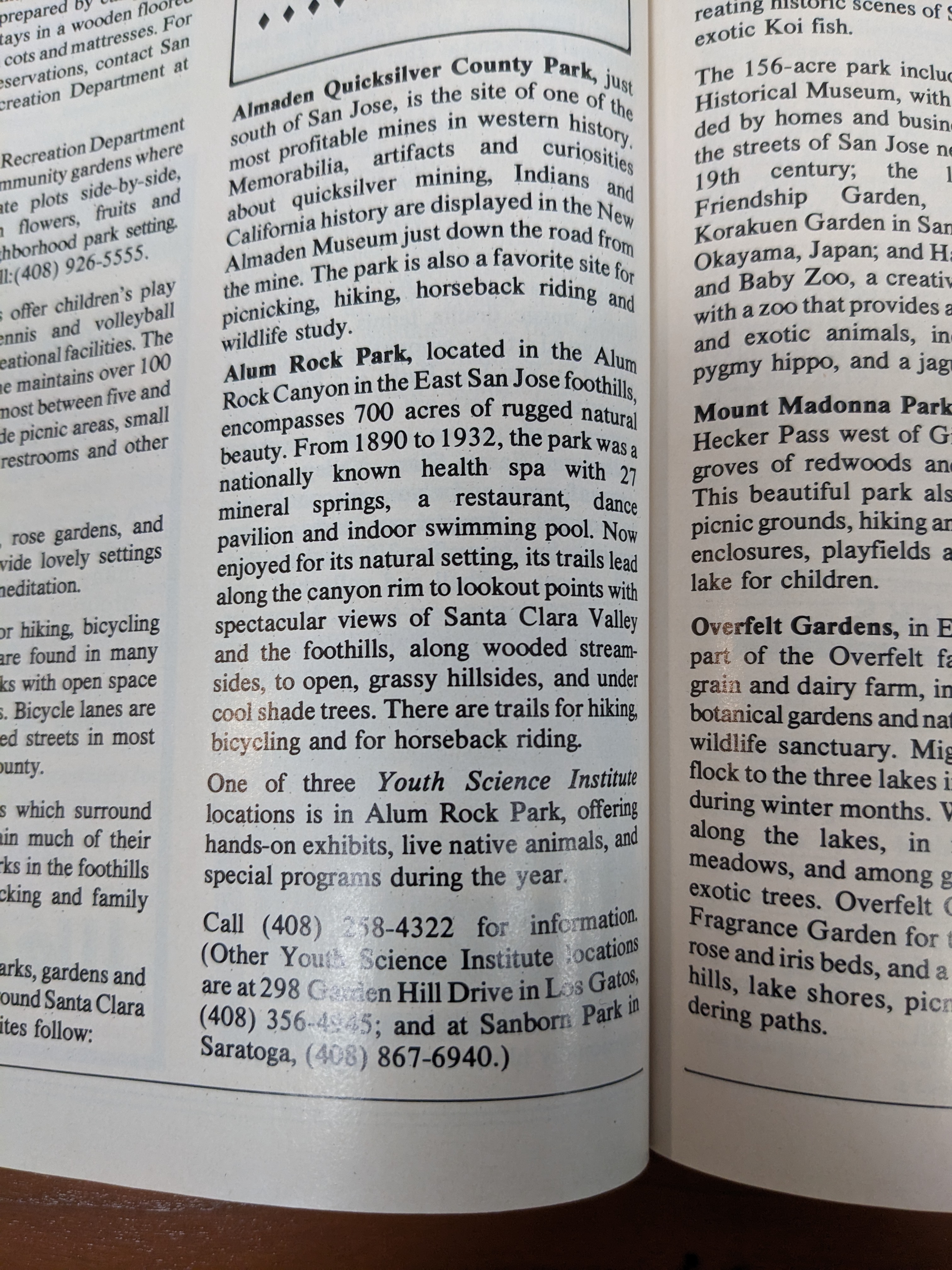

Once the area was back under city control it was determined that the city would continue to develop the health resort and its infrastructure for the benefit of the city's residents. On March 13, 1872, Alum Rock Park was officially established by an Act of the State Legislature and a Park Board of Commissioners was soon created to oversee the management of park affairs. As its first order of business, the Commission oversaw the construction of a new road from the city to the park, which at the time was seven miles past the city limits. Alum Rock Avenue was built in the mid-1870s, providing easy access to the park and mineral springs from the center of the city. The Commission supervised the further improvement of the health resort and the surrounding area throughout the following decade. Pipes and plumbing were installed to control the water flow in several of the springs, the canyon floor was landscaped, exisitng roadways in the park were rebuilt and walking paths were laid out. More structures were built during this time as well, including a gazebo that housed a spring water fountain at its center, bathhouses, dressing rooms, a swimming pool known as "The Plunge," and even a restaurant.

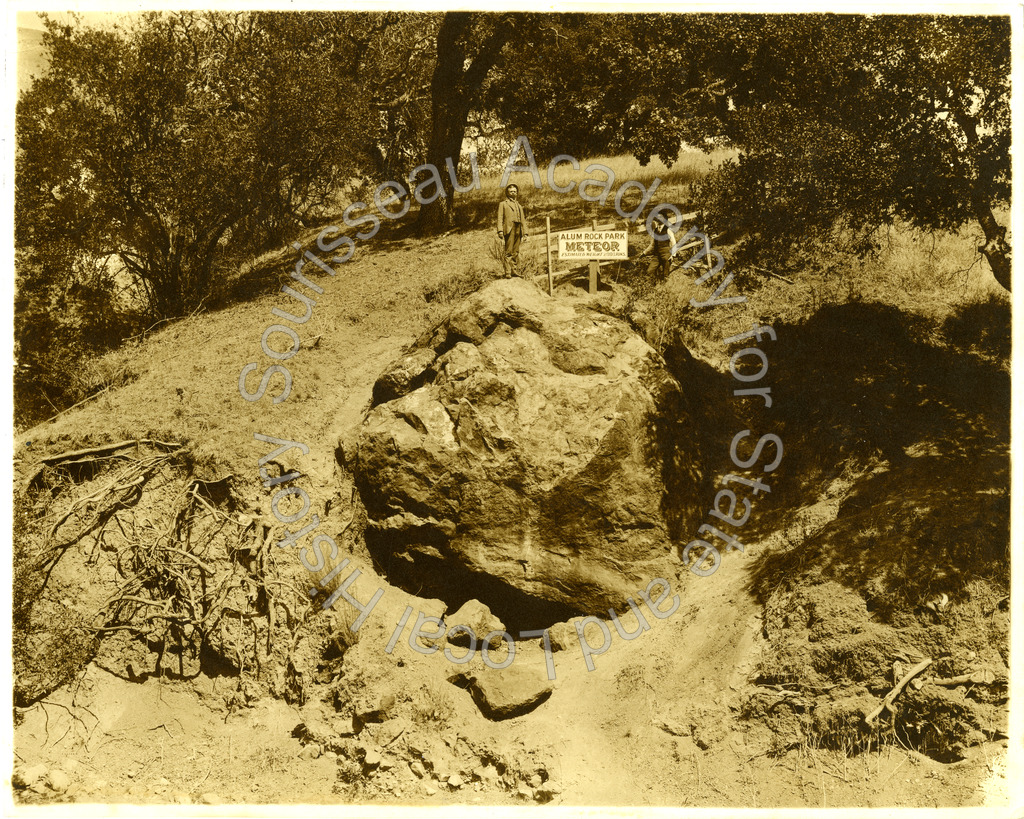

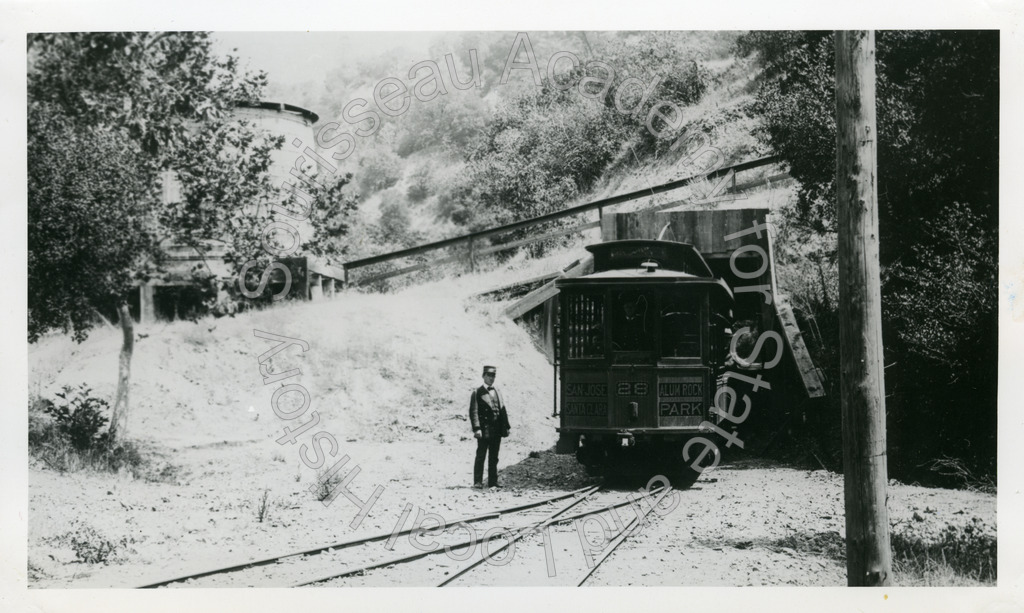

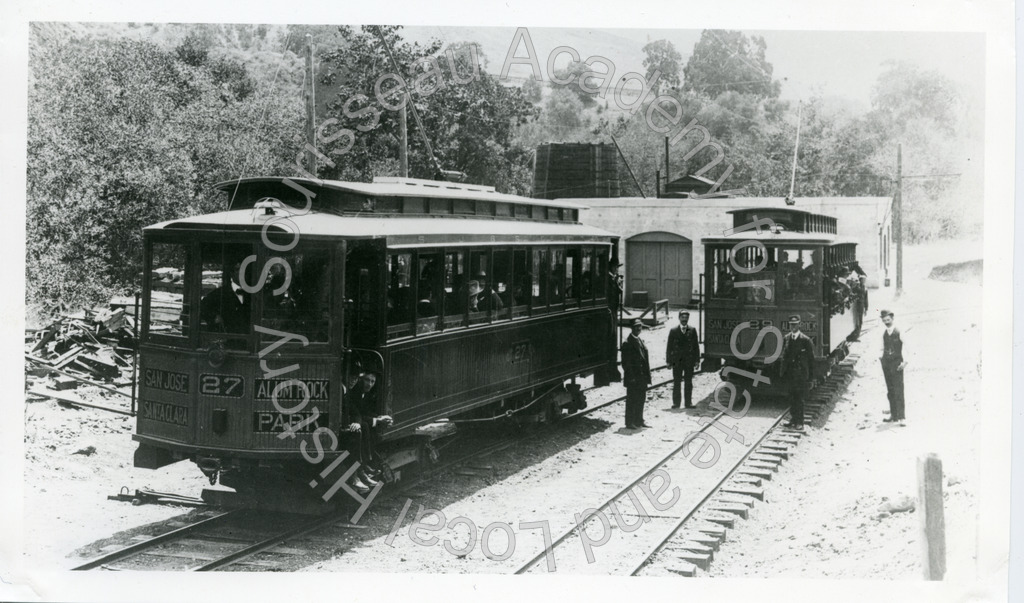

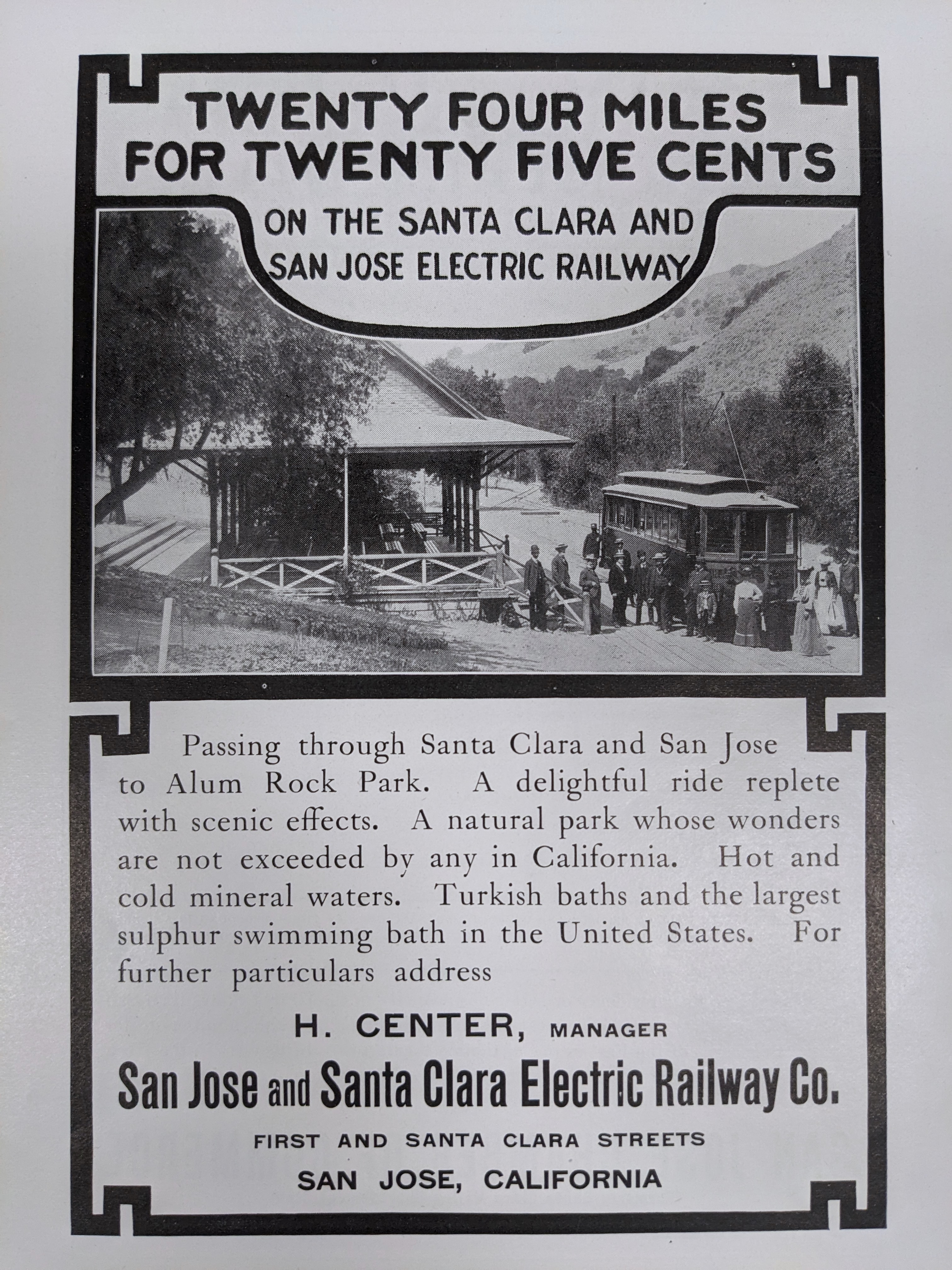

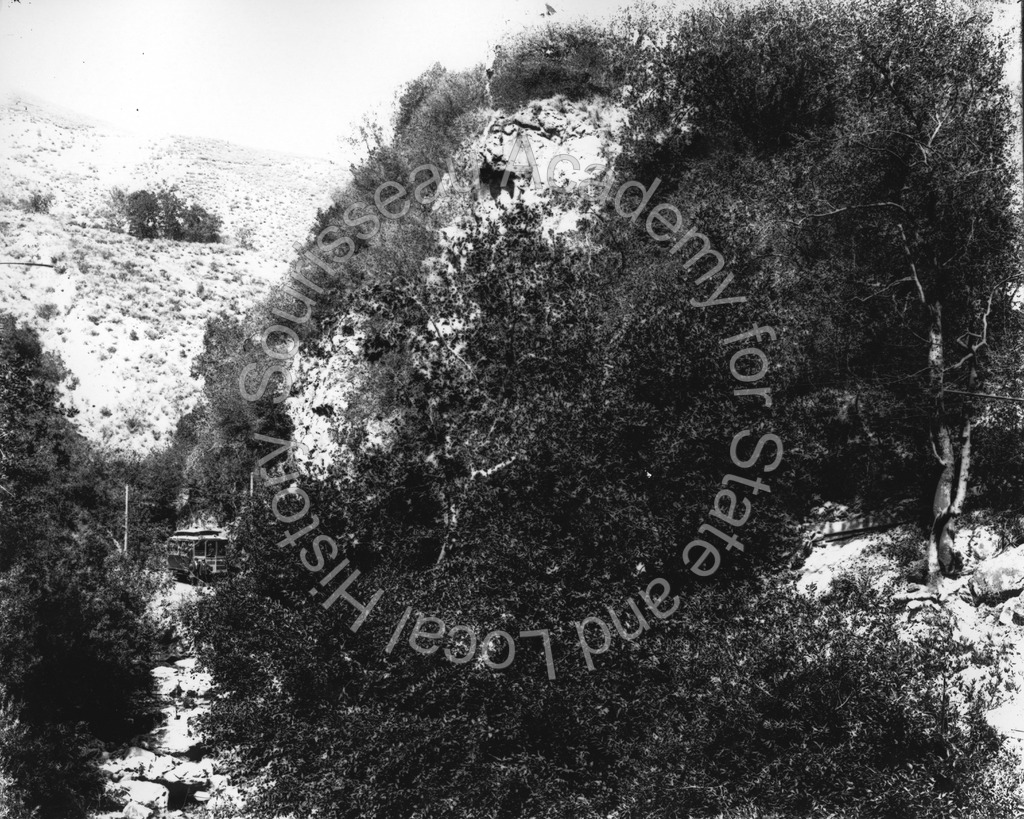

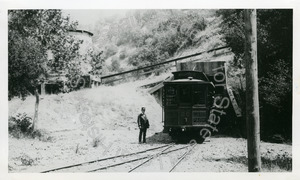

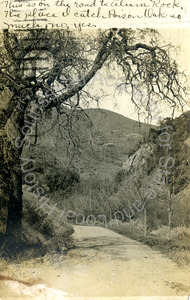

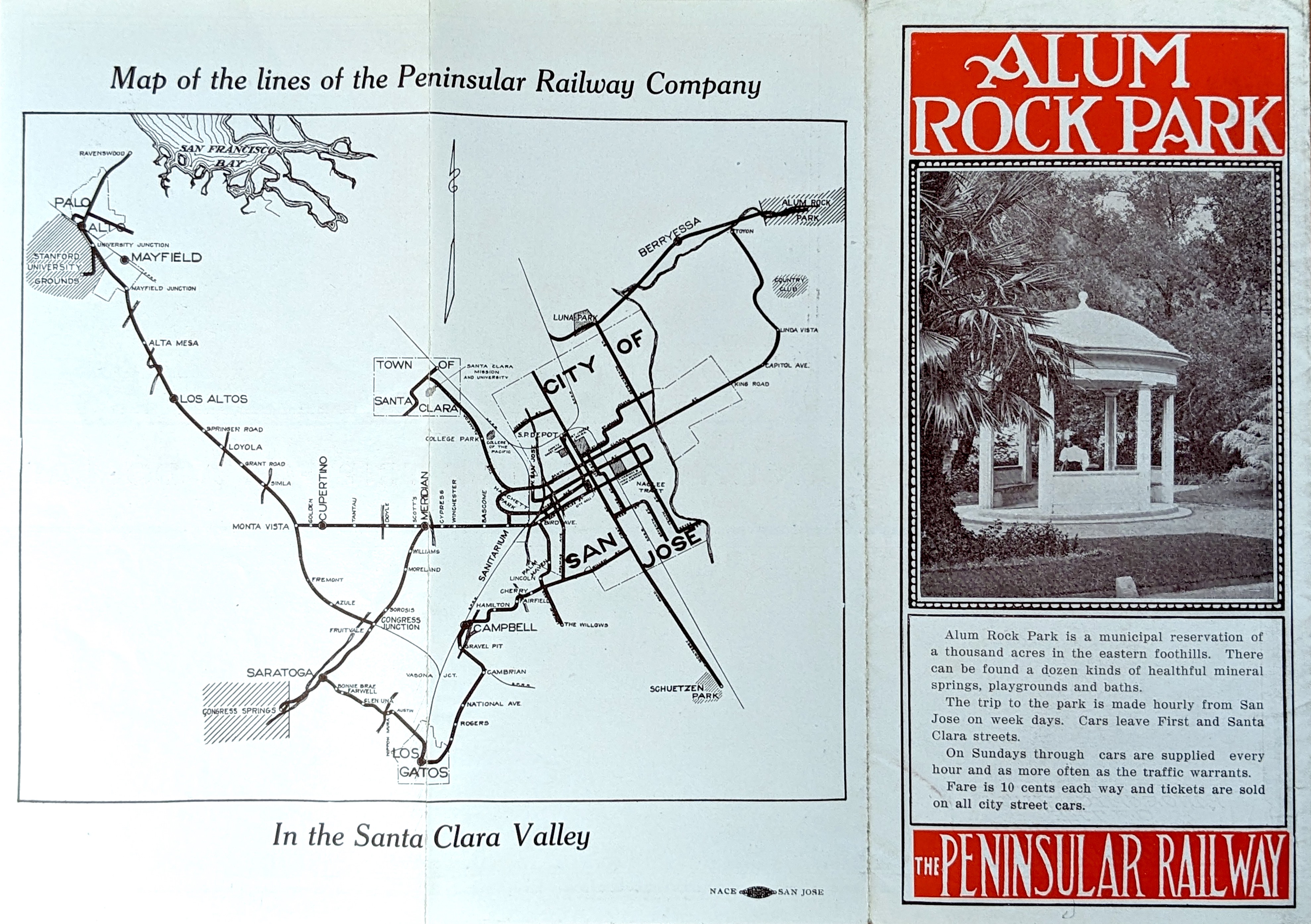

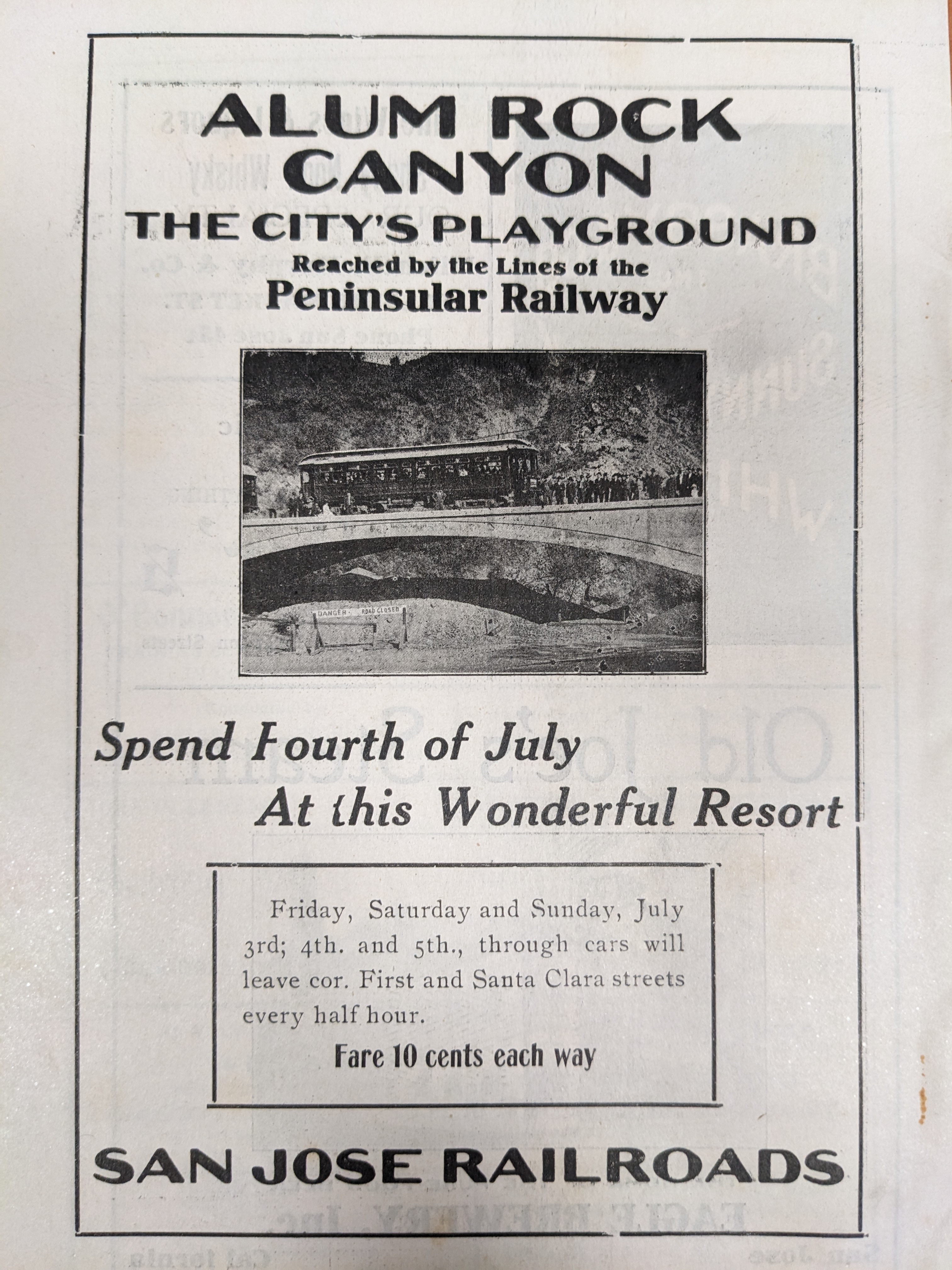

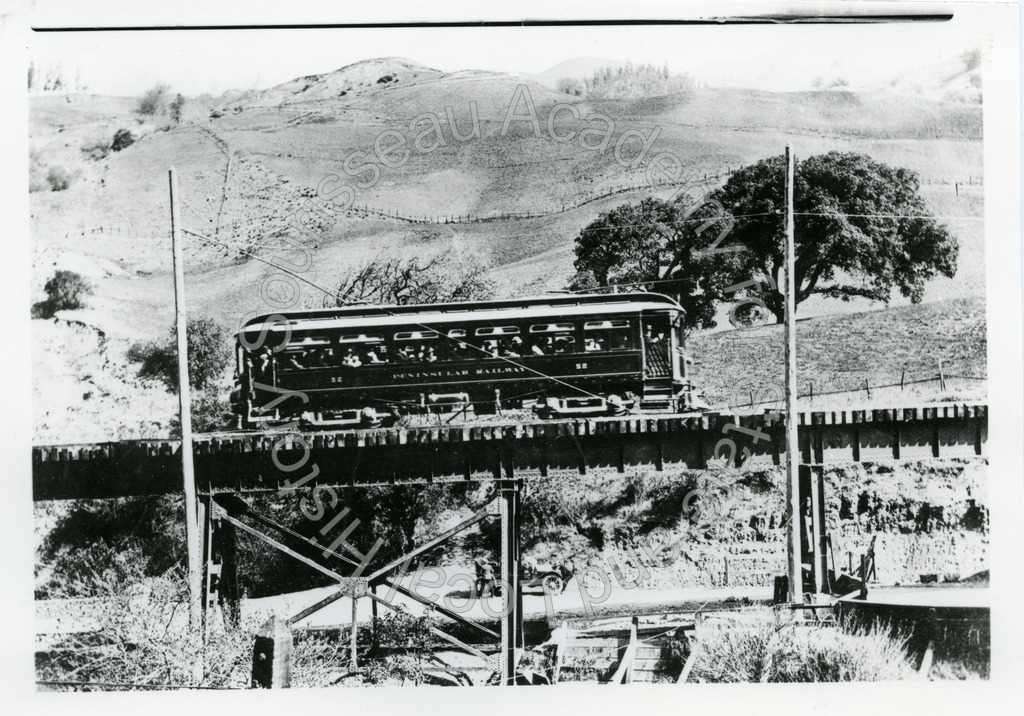

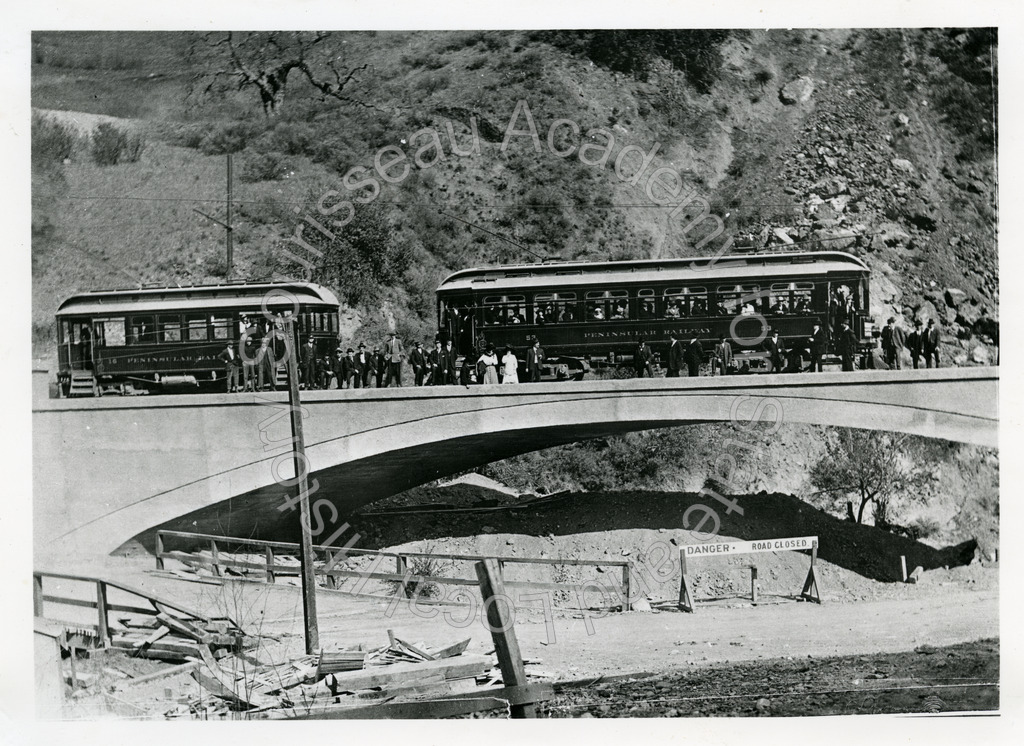

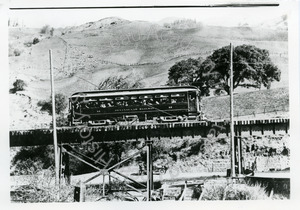

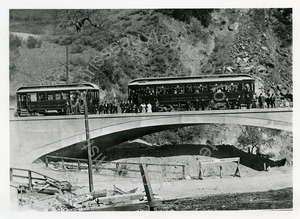

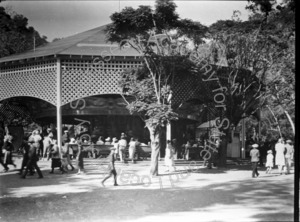

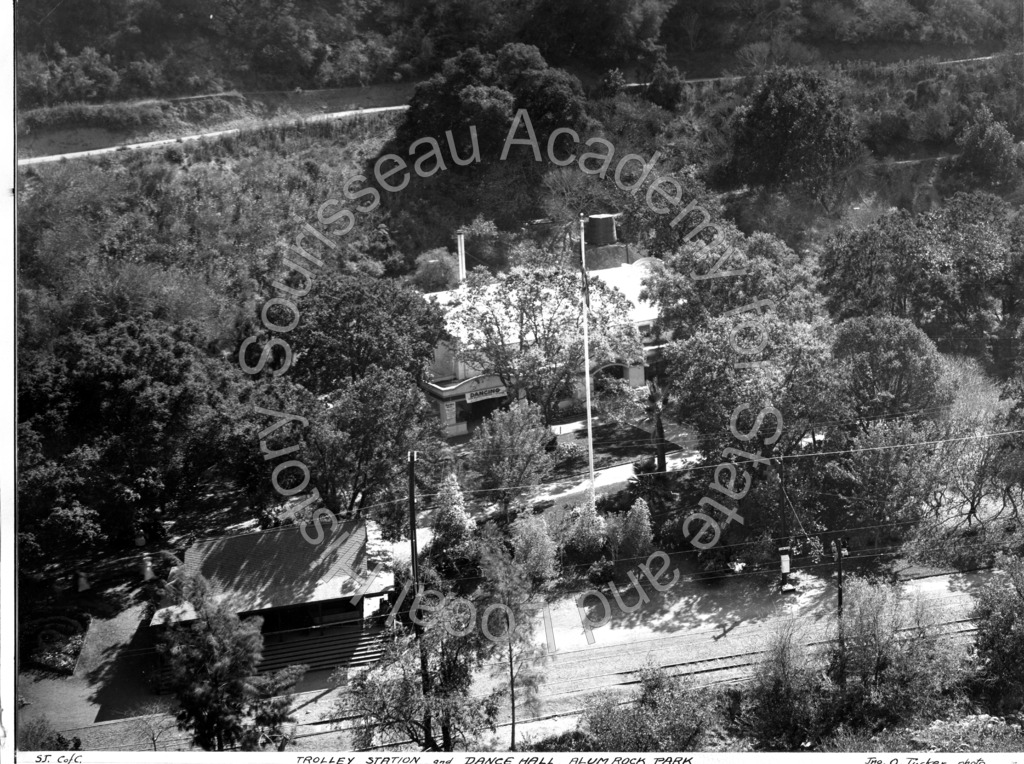

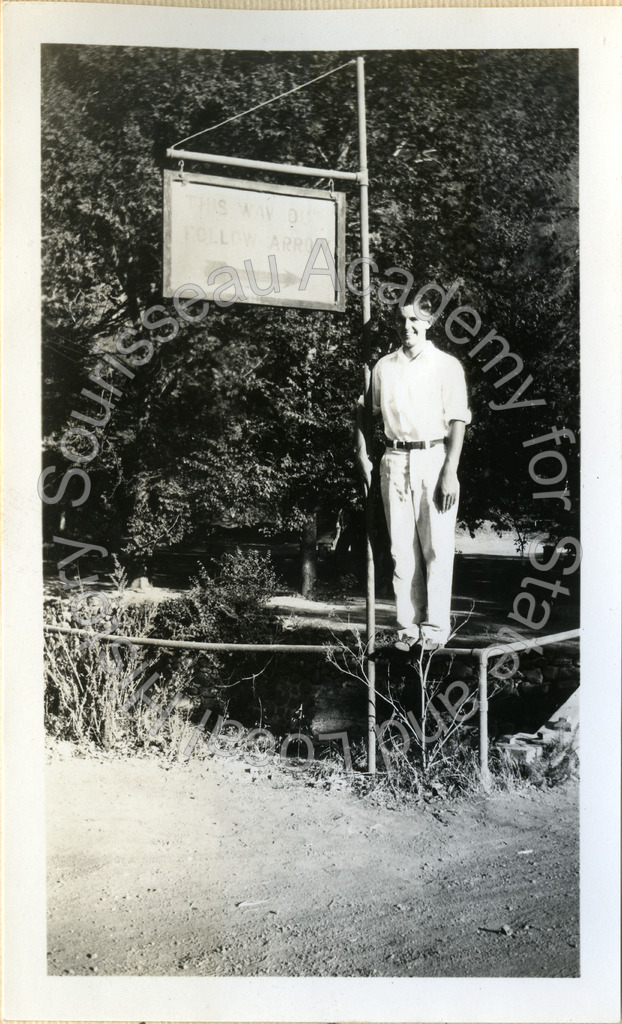

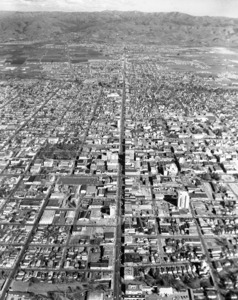

The city further improved public access to the park by permitting the incorporation of The Alum Rock Railway Co., a small, independent trolley company, in 1893. The A.R.R. narrow-gauge tracks ran from First and Santa Clara streets into the canyon, providing the public with a convenient and scenic travel option from the city into Alum Rock Park. Once inside the park, the rails followed and ran alongside Penitencia Creek into the heart of the canyon, where it dropped off its passengers at a depot near the bathhouses. By 1896, these steam-powered trolleys were regularly ferrying visitors to the park’s ever-improving spa and pleasure gardens, passing sights such as an ostrich farm, an olive orchard, and a large rock misidentified for many years as a "meteor" (below).

Early trolley cars were relatively light, small, and equipped with inadequate safety measures, which led to several deaths inside the park in the railroad's early days. Over the years the railroad went through a series of improvements and ownership changes as its popularity grew and ridership soared. The trolleys increased in size and weight to meet demand, and the railroad's incorporation into larger local streetcar networks, such as the Santa Clara and San José Railroad, broadened access to the park. The company phased out the steam powered trolley cars in 1902 when the Alum Rock line was electrified. Though always a pleasure line, the Alum Rock spur of the local streetcar system would continue to serve the public until its closure in 1932.

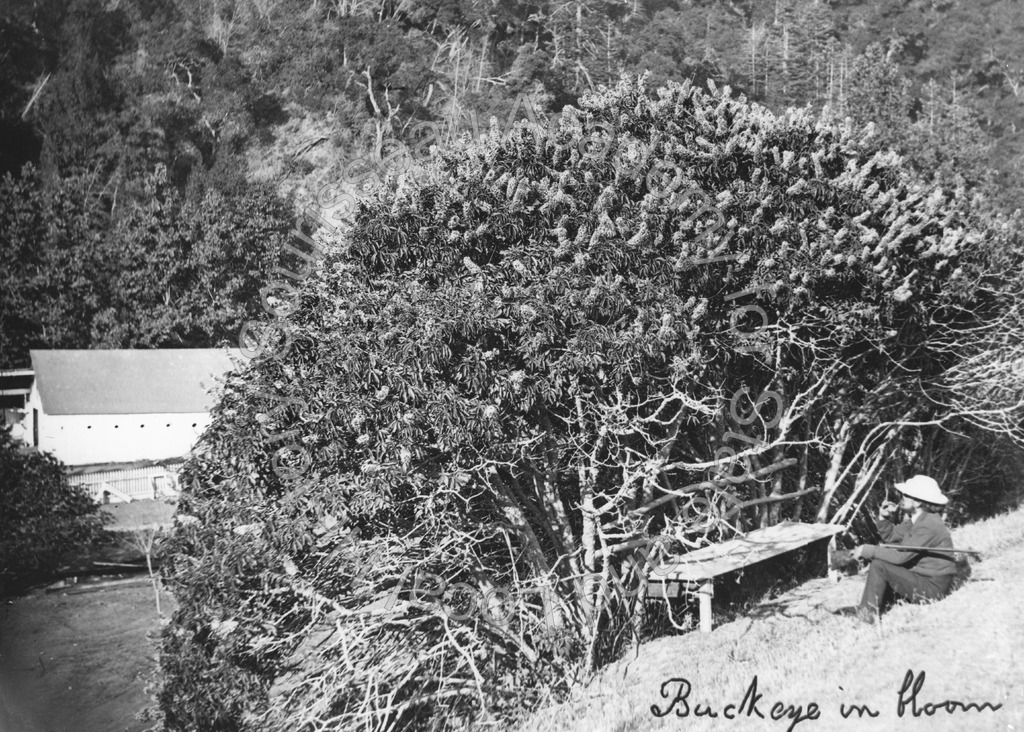

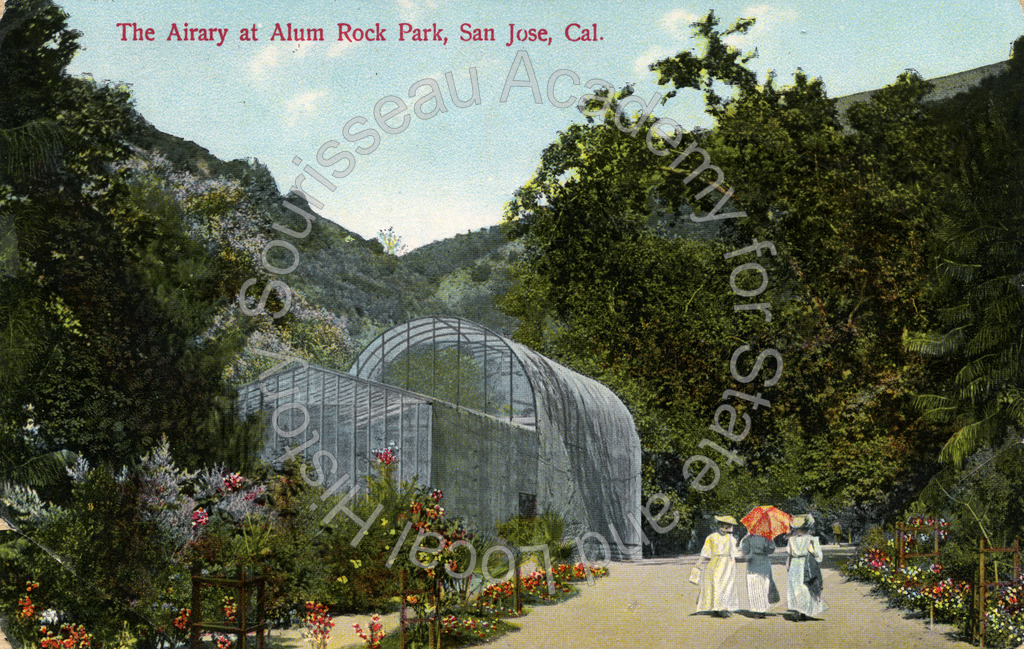

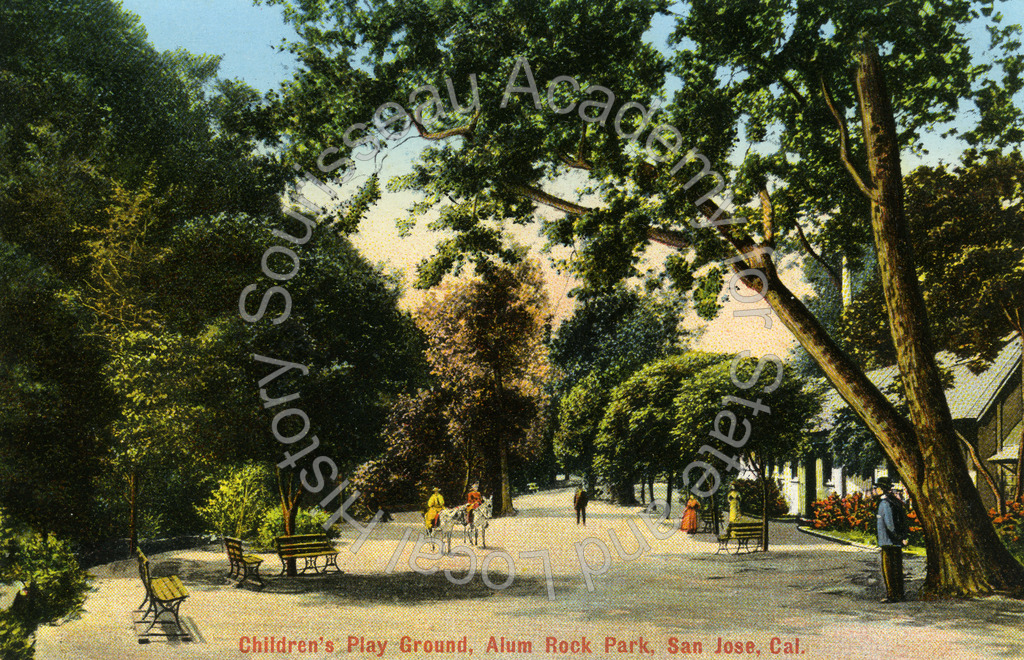

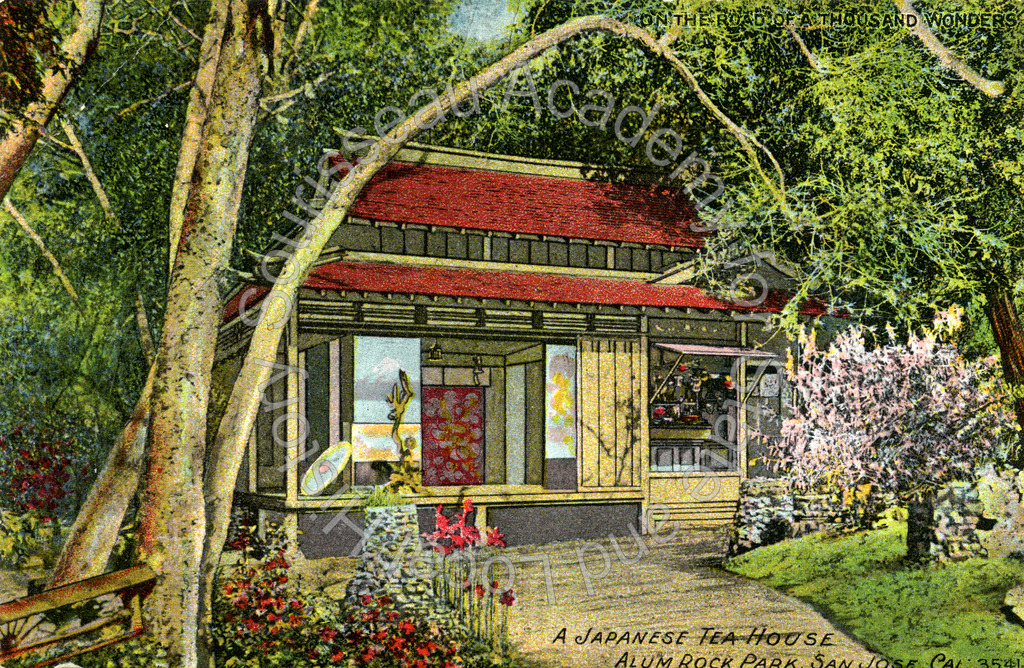

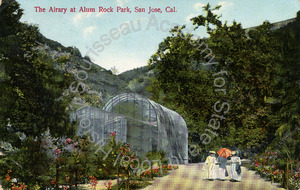

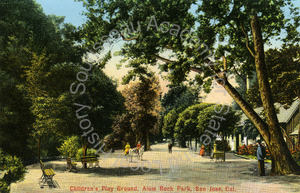

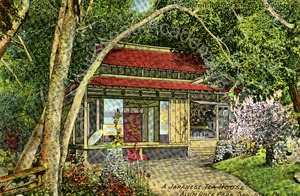

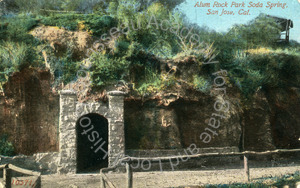

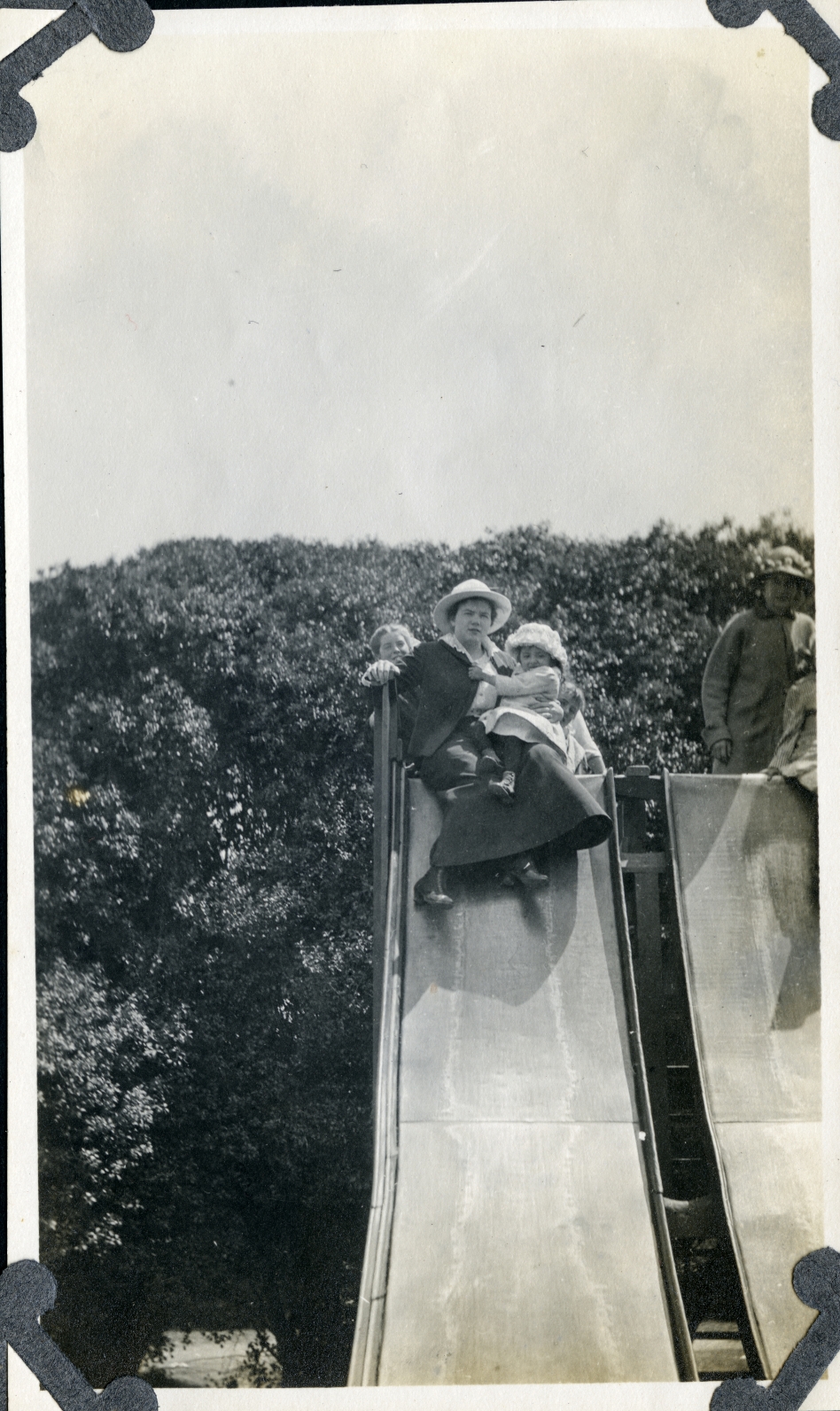

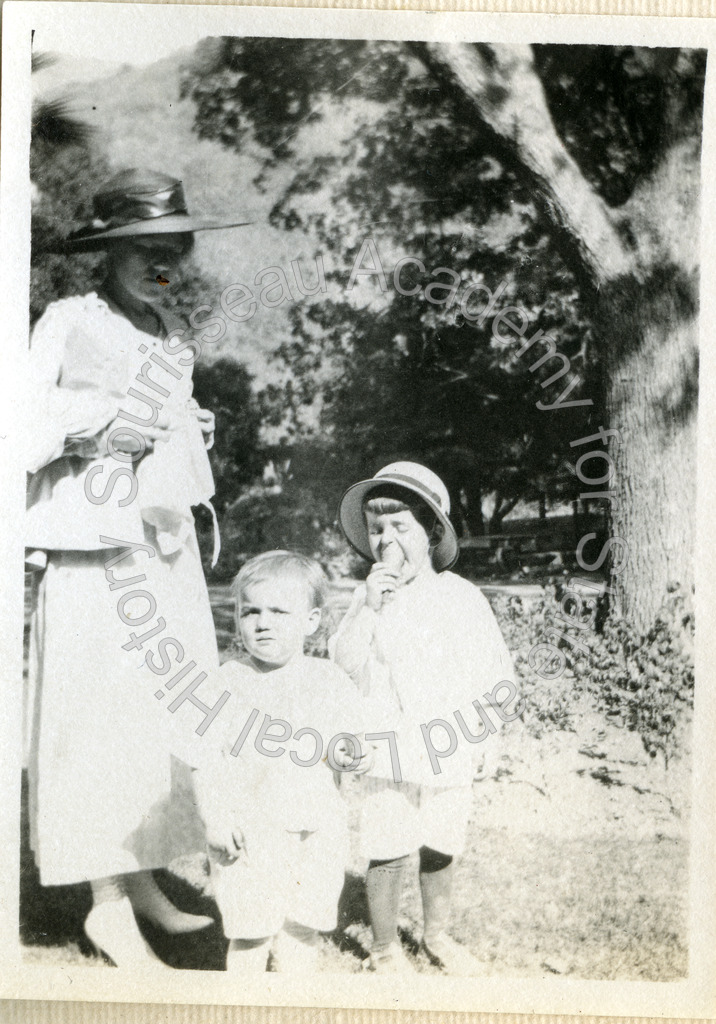

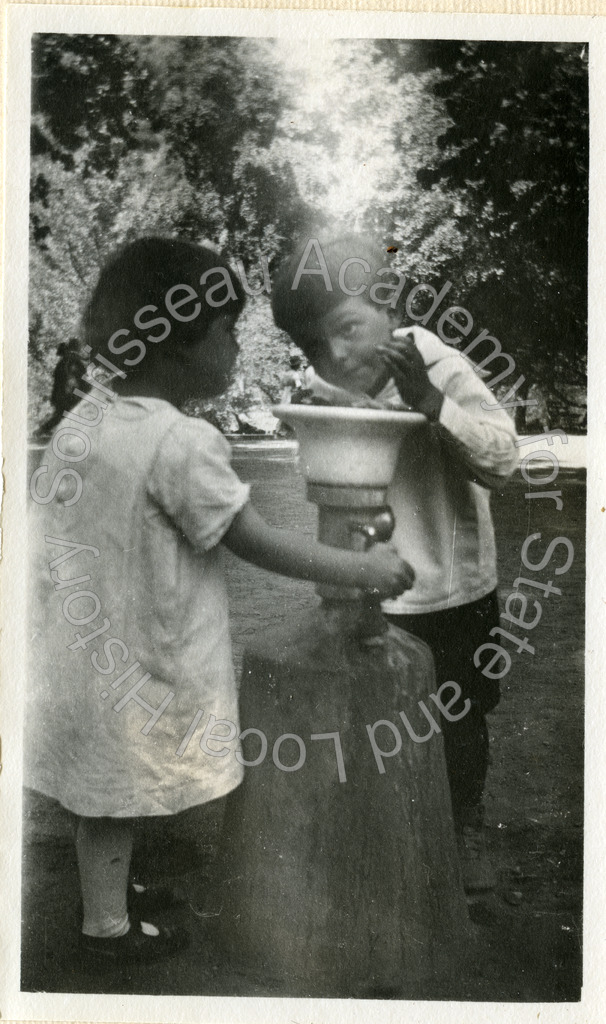

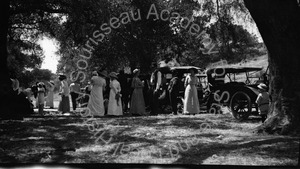

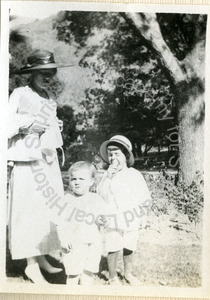

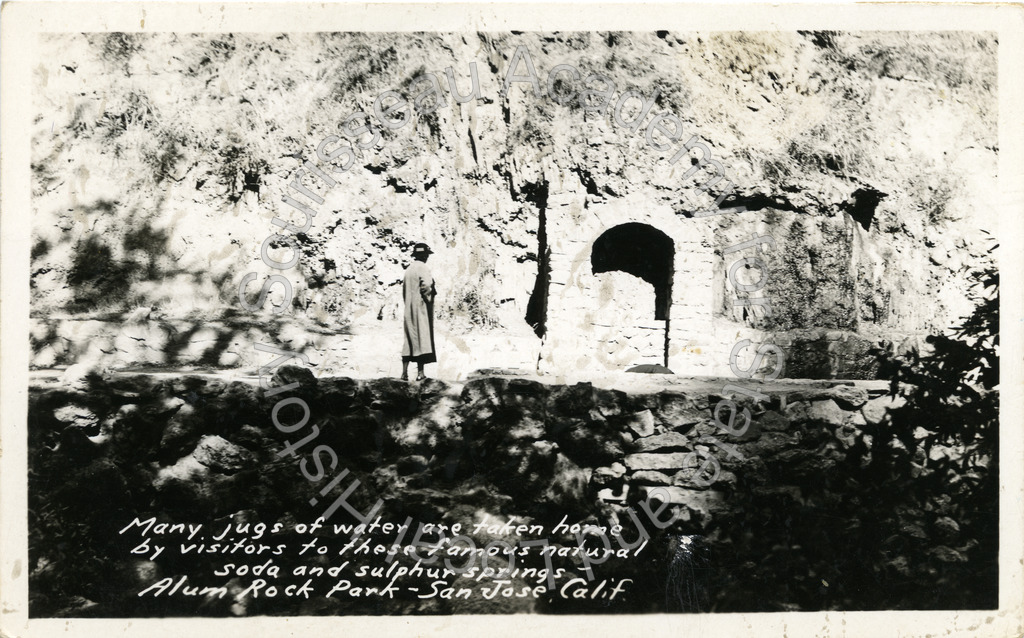

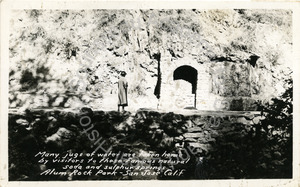

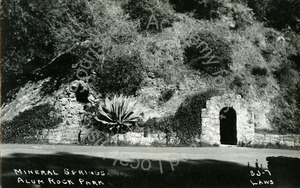

In the late 1800s and early 1900s rapid industrialization and urbanization, as well as poor health and sanitation standards, contributed to a rise in the national demand for public parks and green spaces. Most people still believed in the therapeutic benefits of mineral waters, and with few effective medicines available, mineral spas were popular forms of treatment for many maladies. Alum Rock Park thrived as a result of this public support for the development of mineral spring health spas and city parks. By the first years of the 20th century, the park boasted men’s and women’s bathhouses, a restaurant, aviary, livery stable, children’s playground, Japanese Tea House and Garden, as well as well-maintained walking paths and picnic grounds. The Plunge, initially a large outdoor swimming pool, became the park’s first indoor pool when a “barnlike” structure was built to provide cover. Many of the mineral springs were enclosed in concrete “grottos” and waters with different mineral compositions were piped to the bathhouses and drinking fountains for the convenience of health seekers. All of these health amenities, attractions, and entertainment venues contributed to the continued popularity of Alum Rock Park as a weekend destination for the local community.

Next: An Era of Renewal

An Era of Renewal

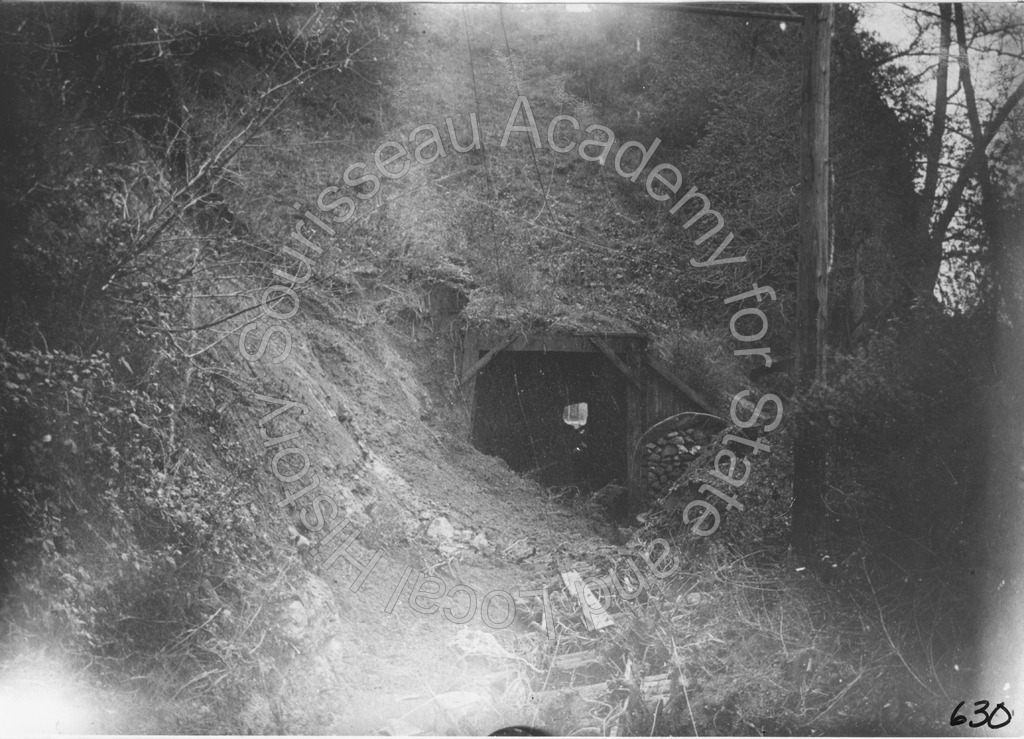

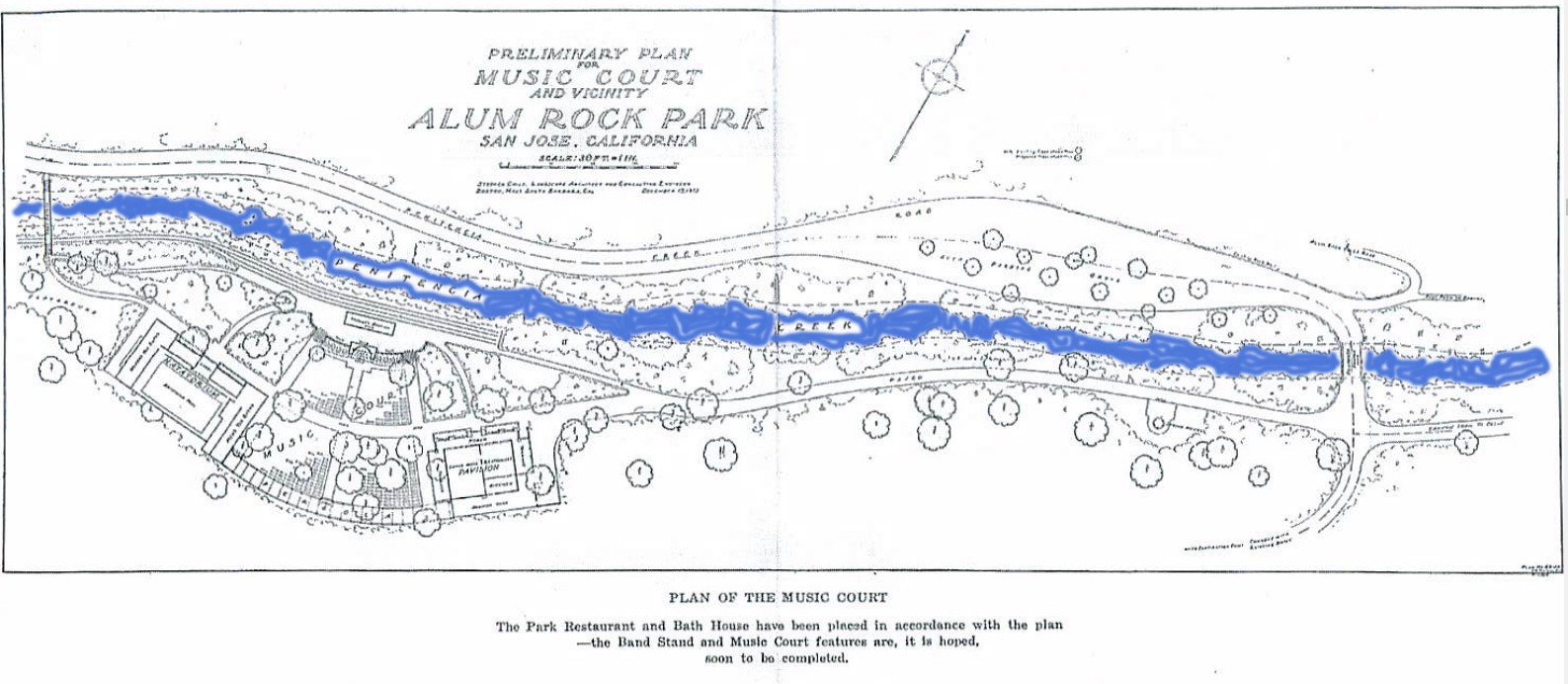

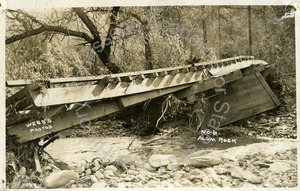

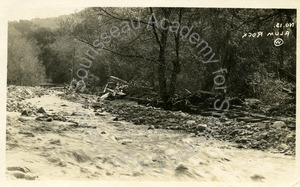

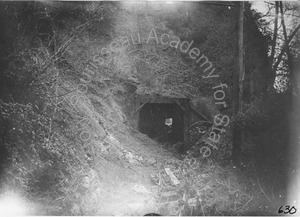

As the park entered its third decade of being a place of local recreation, the City of San José and the Alum Rock Park Commission continued to invest in the development and maintenance of the creek, springs and facilities in the park. Much of that came to a halt when in March of 1911 a severe storm swept through the area, causing flooding in the city as well as in Alum Rock Park, when Penitencia Creek overflowed its banks. The resulting flood in the canyon scoured the canyon floor of many of its buildings and completely destroyed much of the railroad tracks and tunnels in the park. This heavy damage to the park's infrastructure provided the perfect opportunity for the city of San José to reevaluate the ways they were making use of the canyon and and its environs. The Flood of 1911 became the catalyst for a period of renewal inside the park that saw the hiring of Stephen Child, a professional landscape architect, to review the layout, use and infrastructure of the park, and to recommend improvements. Child's final report was submitted to the city in 1916 and included suggestions for the ecological restoration of native plants in the park and along the creek while taking into consideration the railroad access and trails and paths used by park visitors as well as the construction of new facilities and recreation areas.

As the park entered its third decade of being a place of local recreation, the City of San José and the Alum Rock Park Commission continued to invest in the development and maintenance of the creek, springs and facilities in the park. Much of that came to a halt when in March of 1911 a severe storm swept through the area, causing flooding in the city as well as in Alum Rock Park, when Penitencia Creek overflowed its banks. The resulting flood in the canyon scoured the canyon floor of many of its buildings and completely destroyed much of the railroad tracks and tunnels in the park. This heavy damage to the park's infrastructure provided the perfect opportunity for the city of San José to reevaluate the ways they were making use of the canyon and and its environs. The Flood of 1911 became the catalyst for a period of renewal inside the park that saw the hiring of Stephen Child, a professional landscape architect, to review the layout, use and infrastructure of the park, and to recommend improvements. Child's final report was submitted to the city in 1916 and included suggestions for the ecological restoration of native plants in the park and along the creek while taking into consideration the railroad access and trails and paths used by park visitors as well as the construction of new facilities and recreation areas.

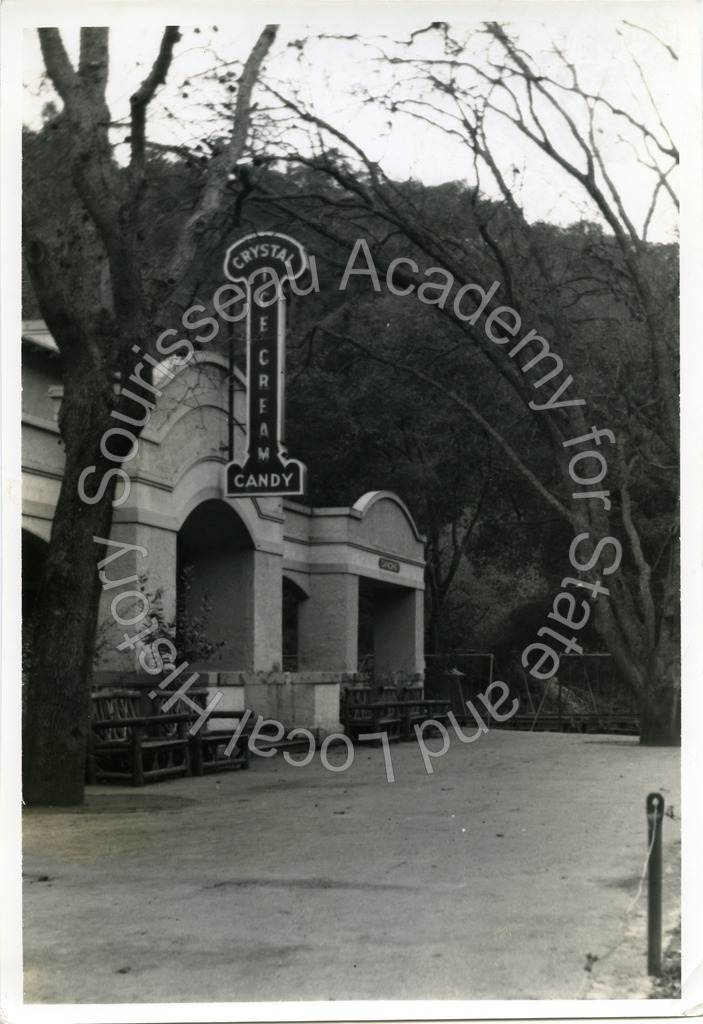

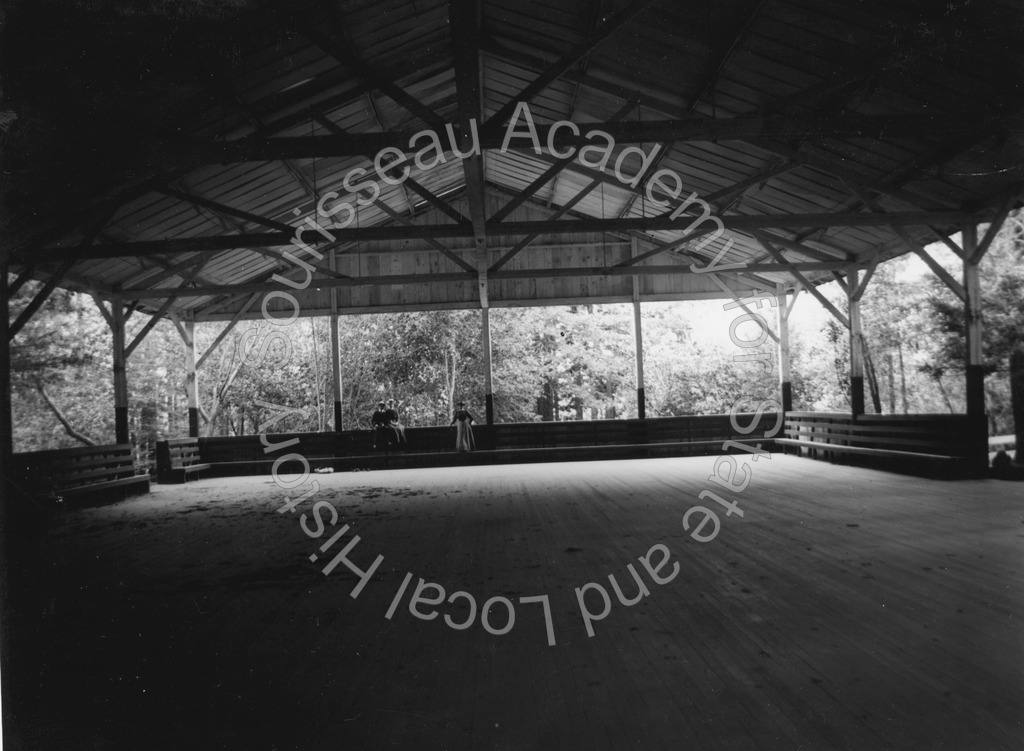

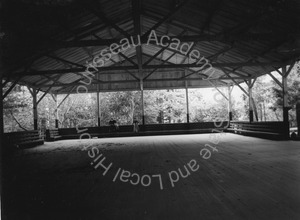

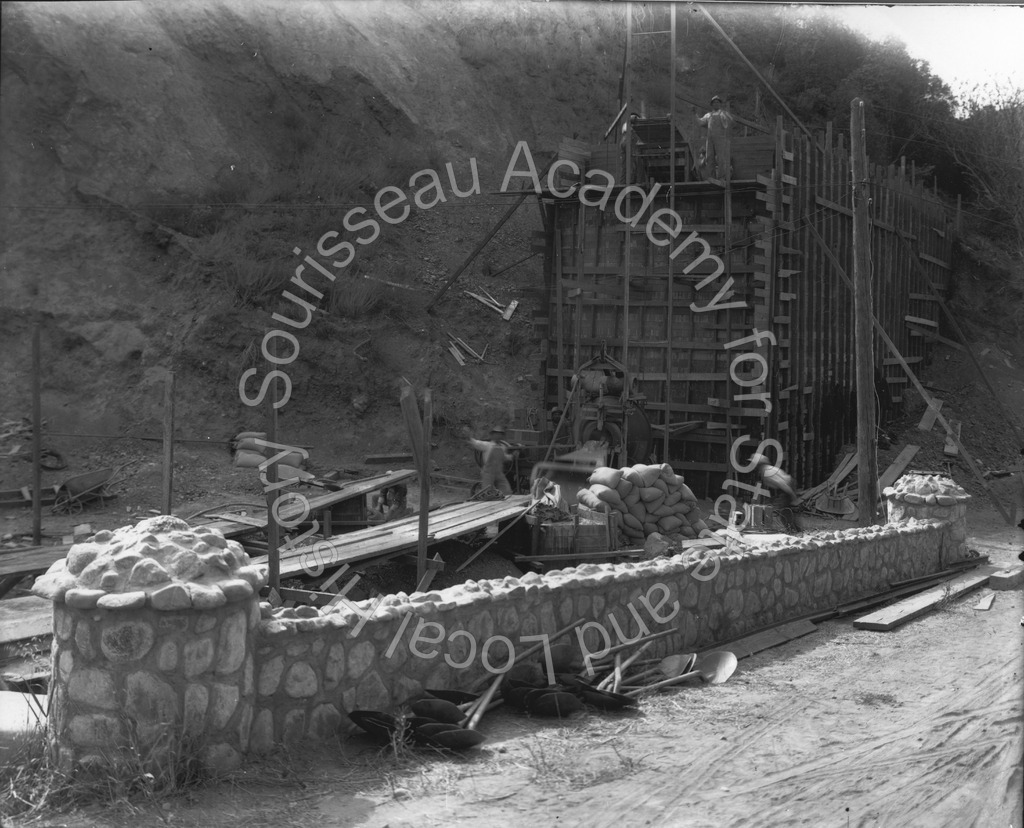

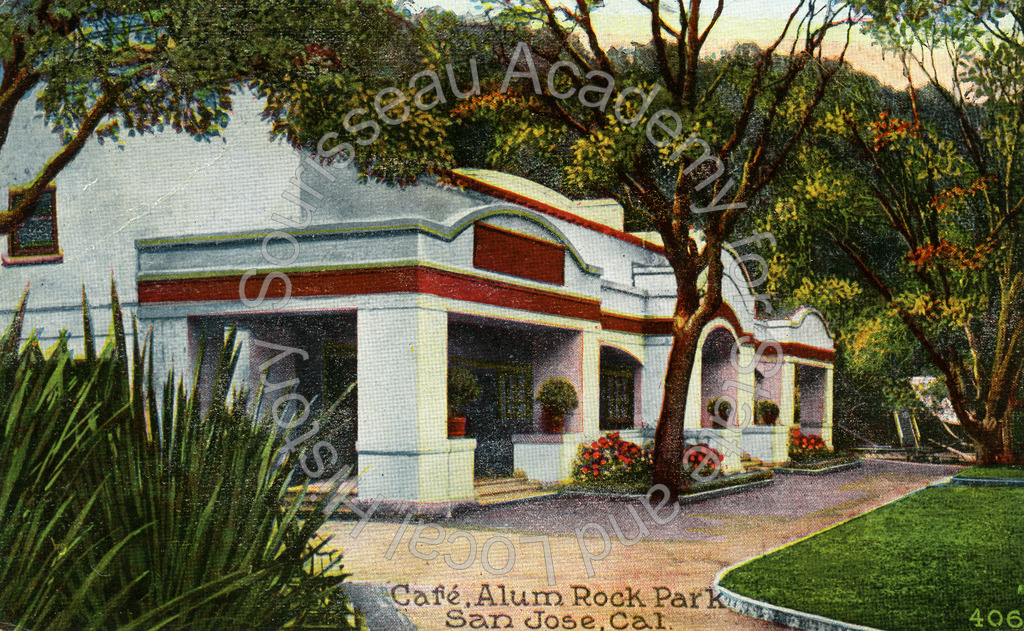

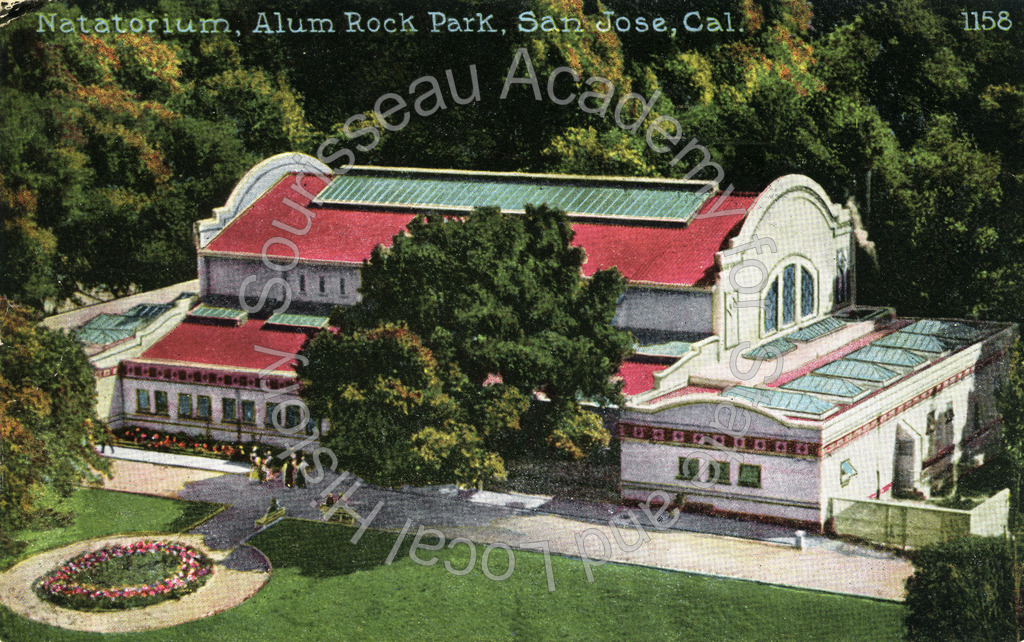

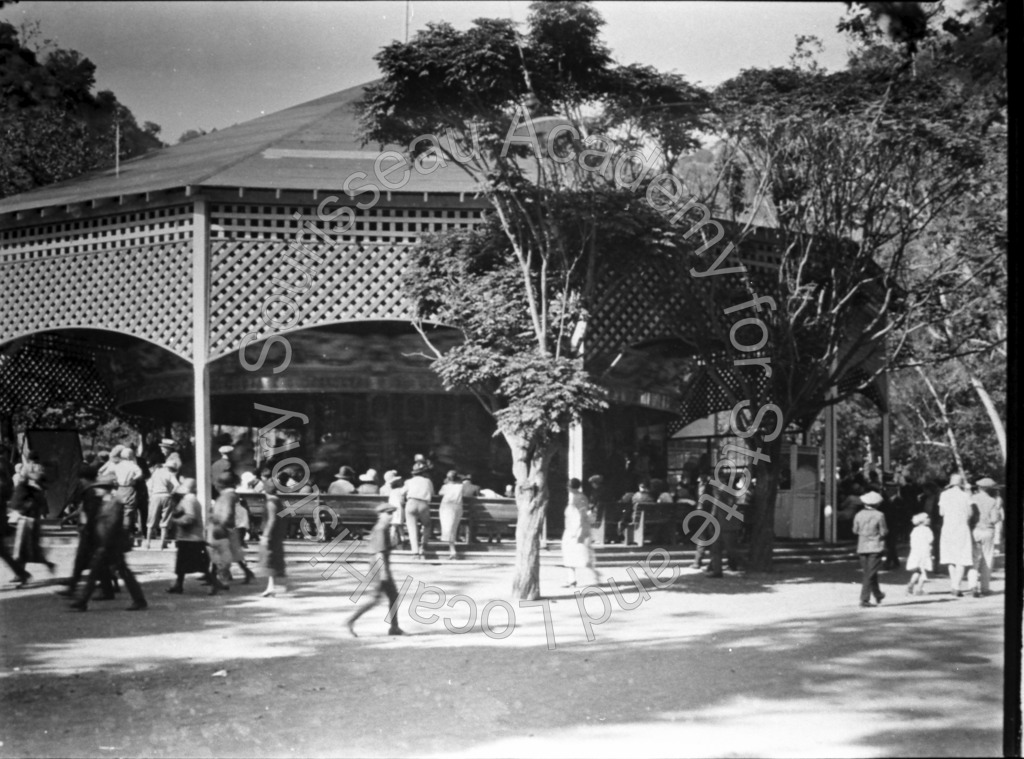

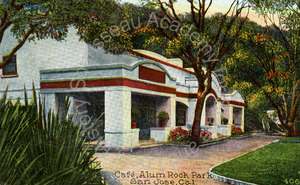

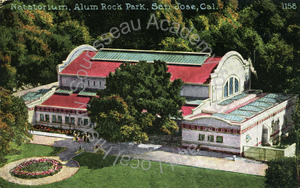

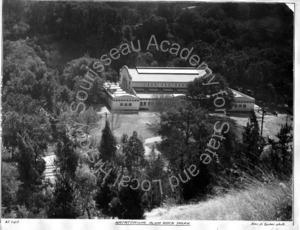

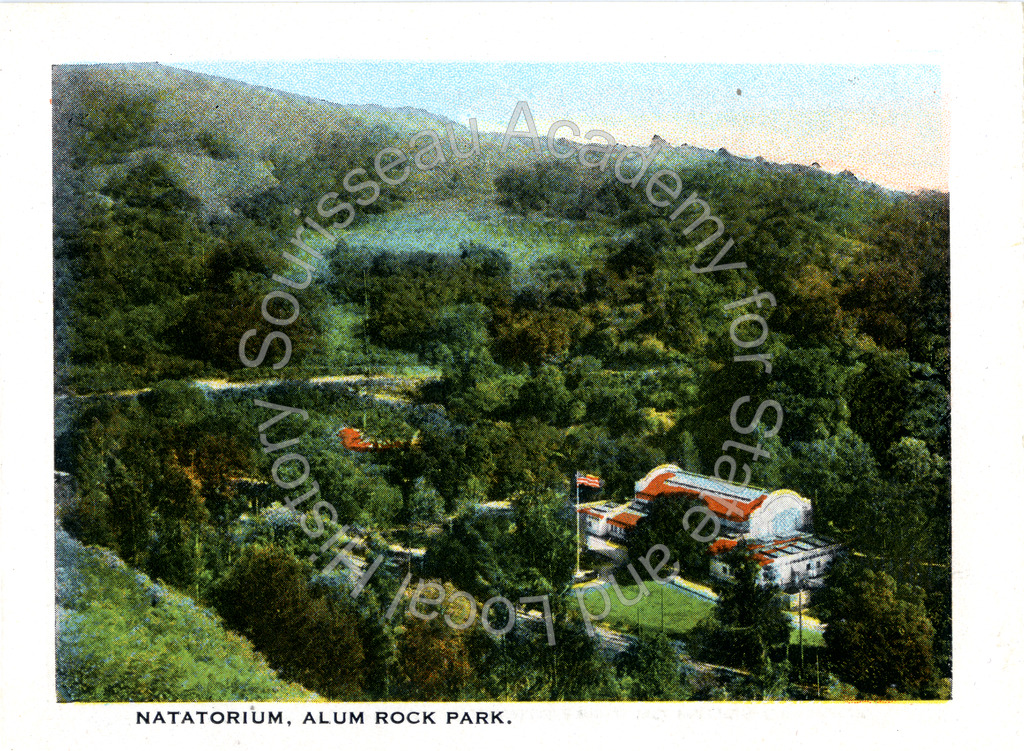

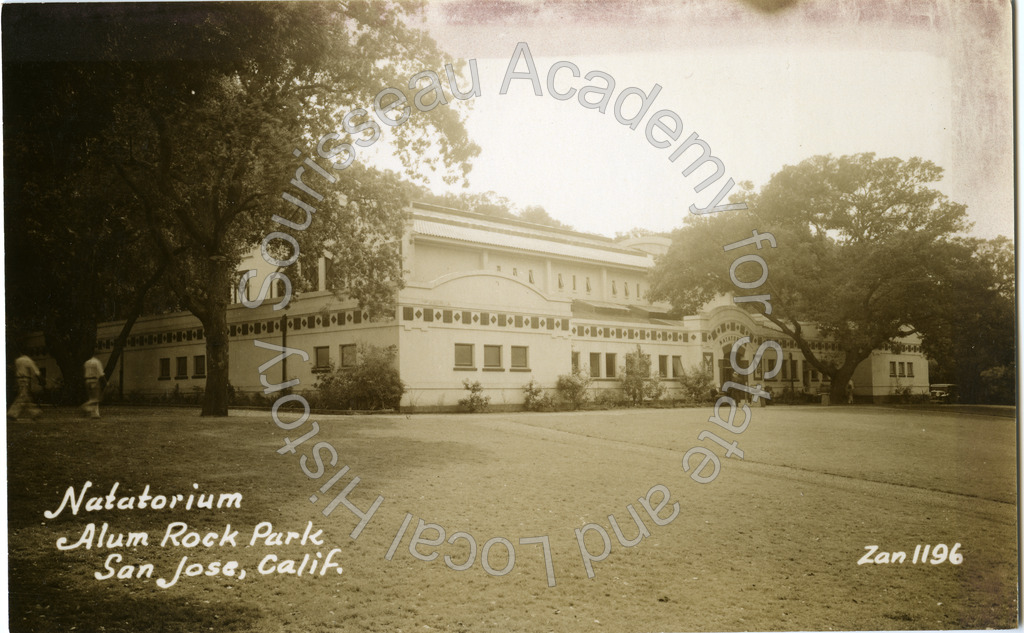

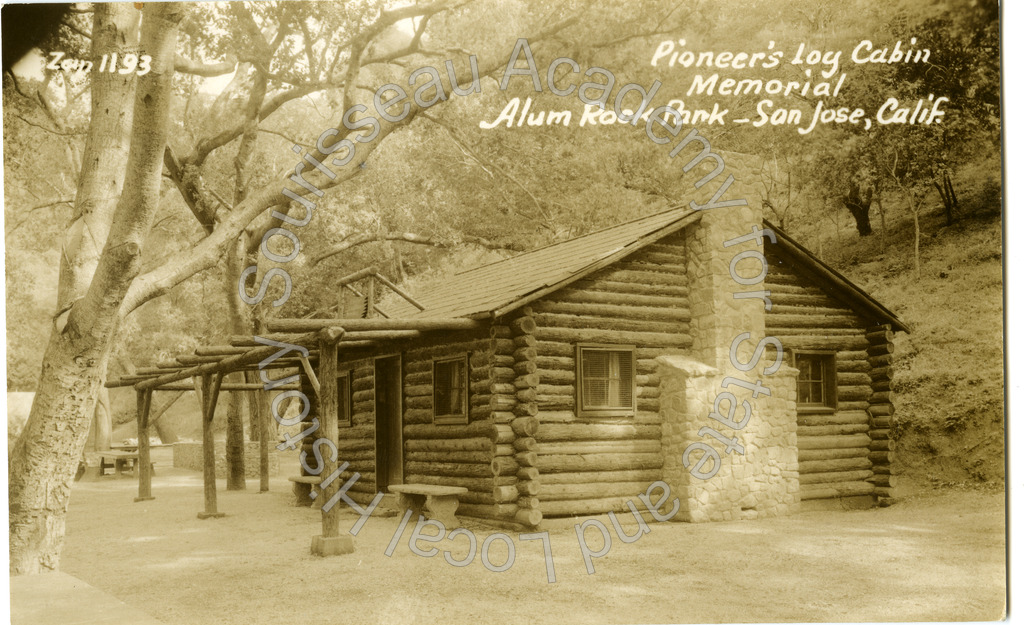

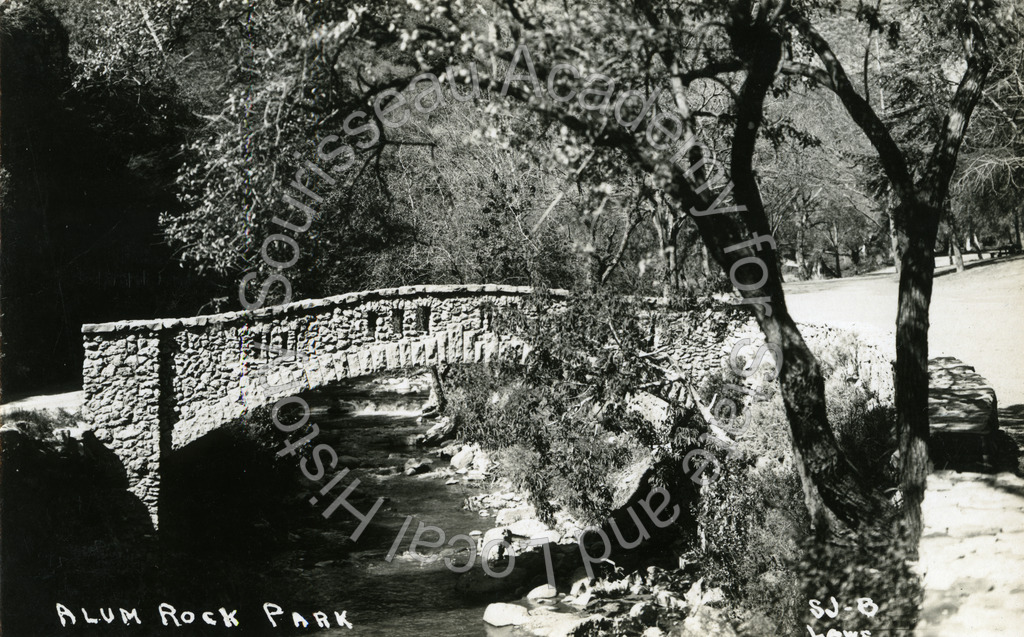

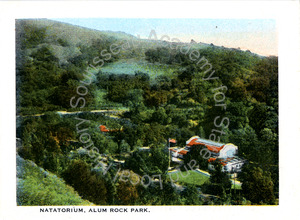

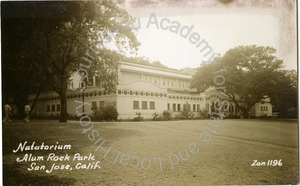

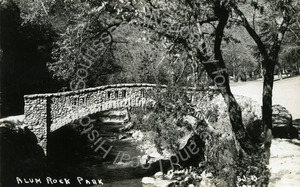

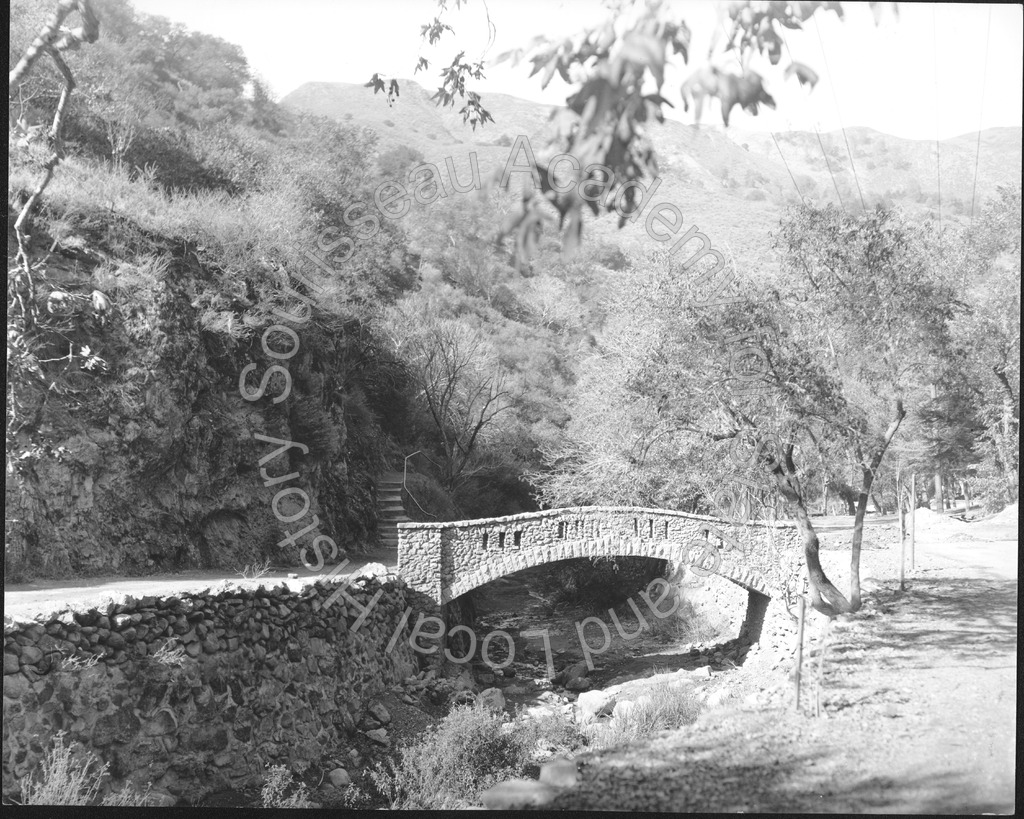

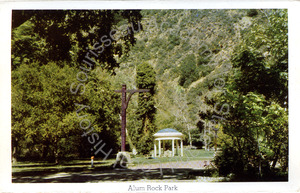

When construction of new broad-gauge tracks in the existing railroad bed began, trestles and concrete bridges were installed in the park in order to avoid future flood damage to the lines. The attitudes toward park design and use had shifted since the late-nineteenth century and the public now wanted opportunities for more active forms of recreation rather than the relaxing bathhouses and quiet pleasure gardens of the past. When rebuilding the park facilities, the Park Commission chose to focus more on family-friendly entertainment than on the health spa aspect although mineral baths and the spring-fed drinking fountain under the gazebo (also called the pagoda in early years) would still be in use for decades to come. Many new amenities were built in the following several years, such as the Natatorium, a combination Café and Dance Pavilion building, a carousel, a new aviary, deer paddock, and the Pioneer Log Cabin replica. Families were encouraged to enjoy the paths, trails and picnic grounds during the day, and the campgrounds and freshwater fountains made overnight stays in the park possible. Eventually, entry into World War I in 1917 caused this rapid park redevelopment to stall for several years although visitor numbers were not significantly impacted.

When construction of new broad-gauge tracks in the existing railroad bed began, trestles and concrete bridges were installed in the park in order to avoid future flood damage to the lines. The attitudes toward park design and use had shifted since the late-nineteenth century and the public now wanted opportunities for more active forms of recreation rather than the relaxing bathhouses and quiet pleasure gardens of the past. When rebuilding the park facilities, the Park Commission chose to focus more on family-friendly entertainment than on the health spa aspect although mineral baths and the spring-fed drinking fountain under the gazebo (also called the pagoda in early years) would still be in use for decades to come. Many new amenities were built in the following several years, such as the Natatorium, a combination Café and Dance Pavilion building, a carousel, a new aviary, deer paddock, and the Pioneer Log Cabin replica. Families were encouraged to enjoy the paths, trails and picnic grounds during the day, and the campgrounds and freshwater fountains made overnight stays in the park possible. Eventually, entry into World War I in 1917 caused this rapid park redevelopment to stall for several years although visitor numbers were not significantly impacted.

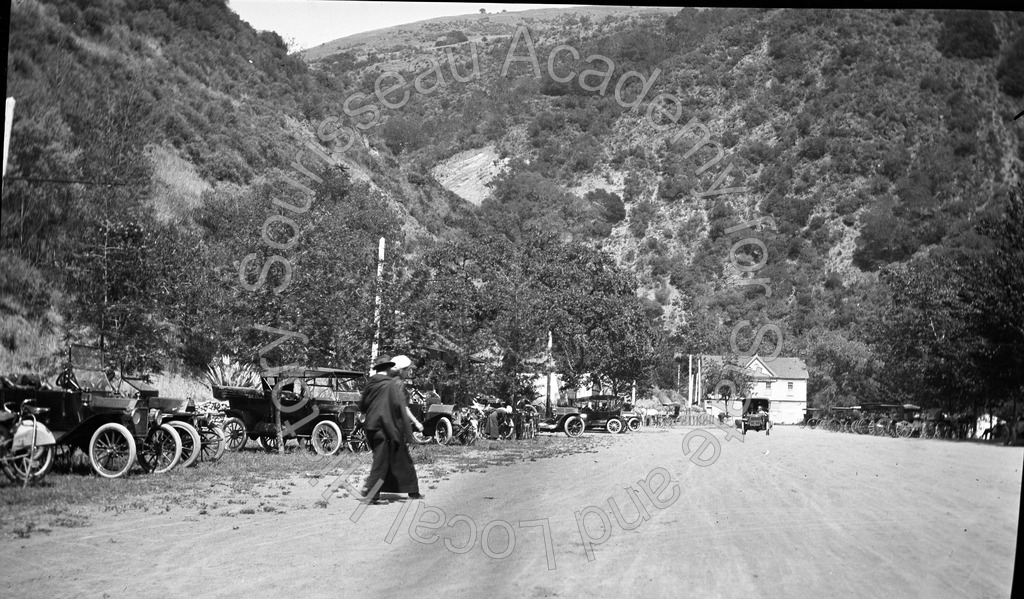

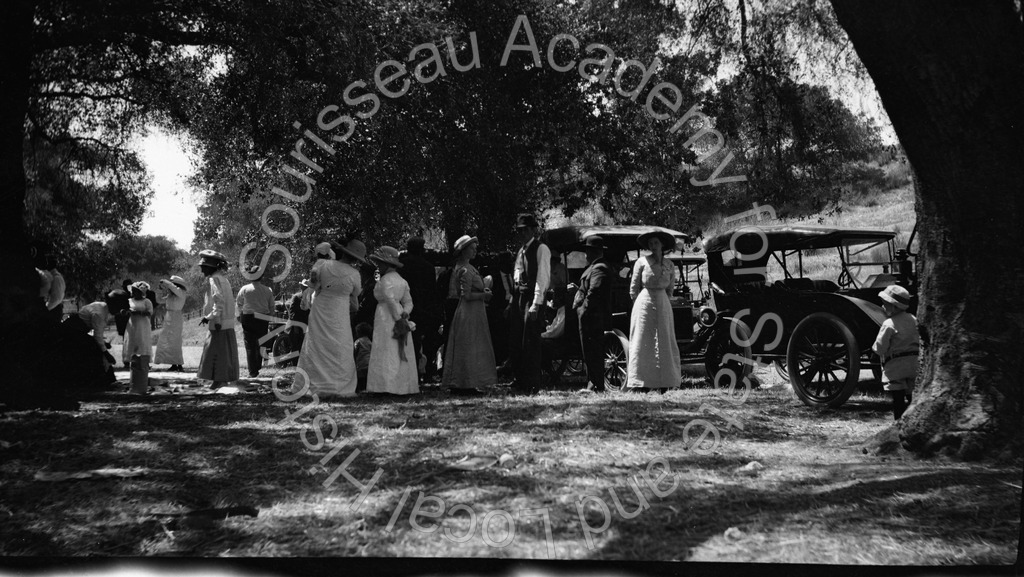

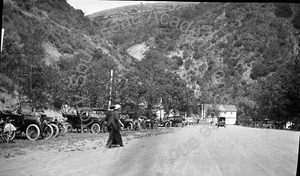

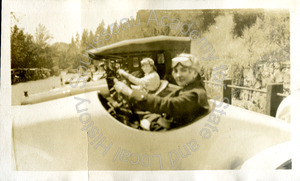

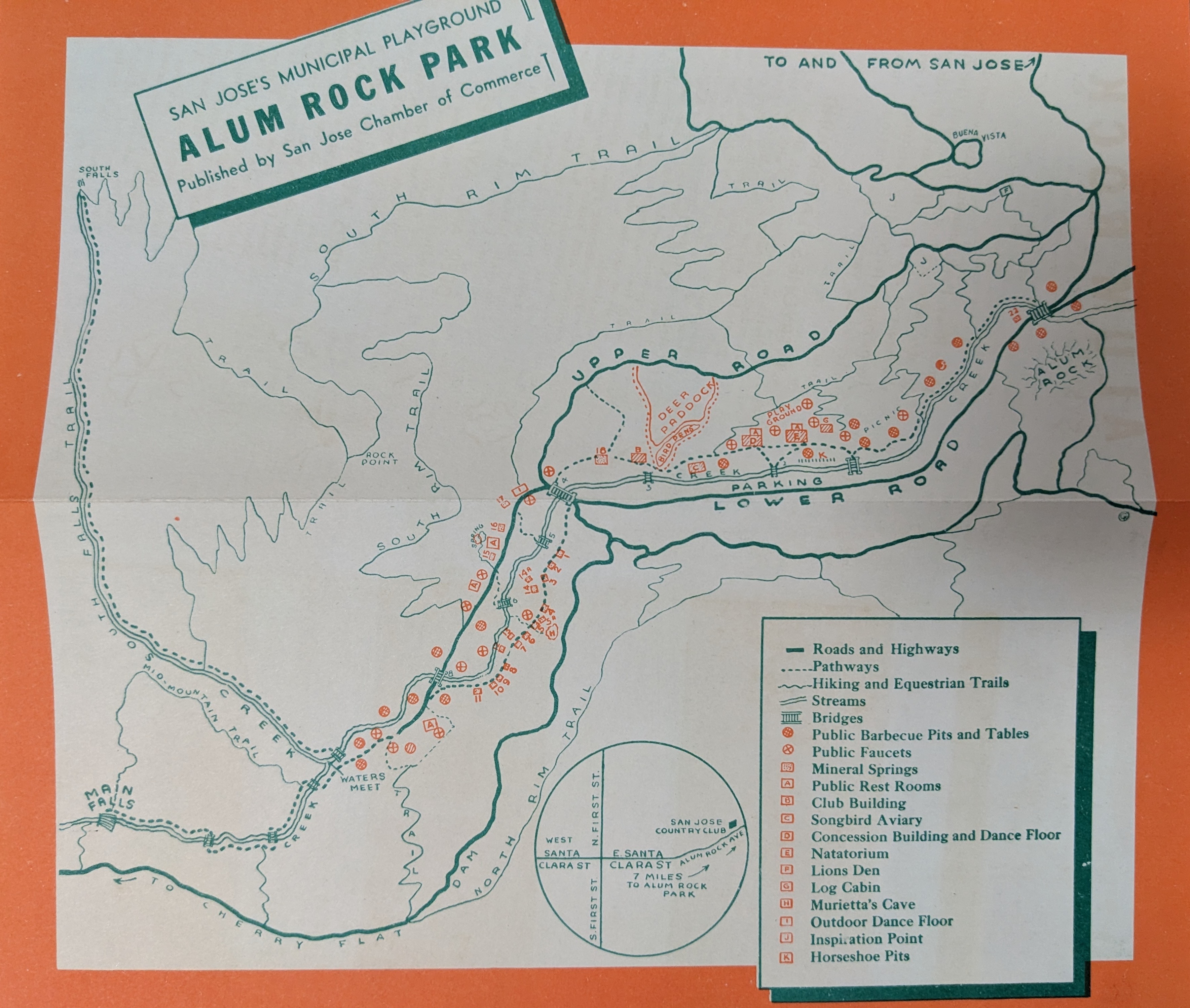

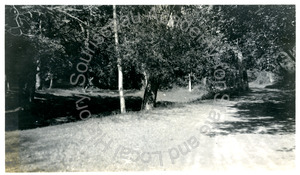

During these early years of the 20th century the automobile was increasingly taking over as the dominant mode of transportation to the park. Unlike today’s single road in and out, visitors could drive in a loop around the heart of the park, and even drive up to some of the picnic grounds in the Mineral Springs area. The park began to be touted as one of the valley’s driving tour destinations in city government and Chamber of Commerce brochures as well as in guides to the larger Bay Area.

During these early years of the 20th century the automobile was increasingly taking over as the dominant mode of transportation to the park. Unlike today’s single road in and out, visitors could drive in a loop around the heart of the park, and even drive up to some of the picnic grounds in the Mineral Springs area. The park began to be touted as one of the valley’s driving tour destinations in city government and Chamber of Commerce brochures as well as in guides to the larger Bay Area.

Next: New Directions

New Directions

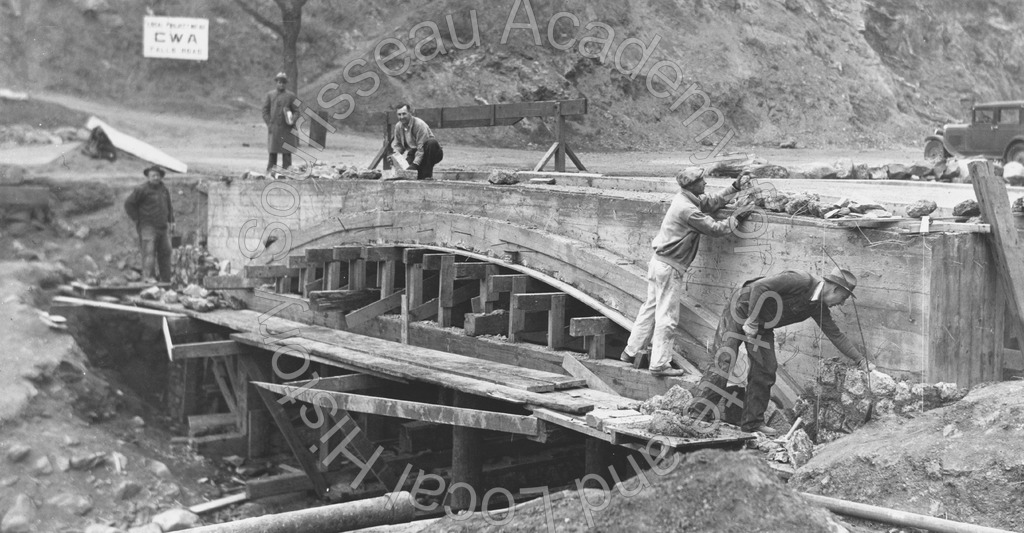

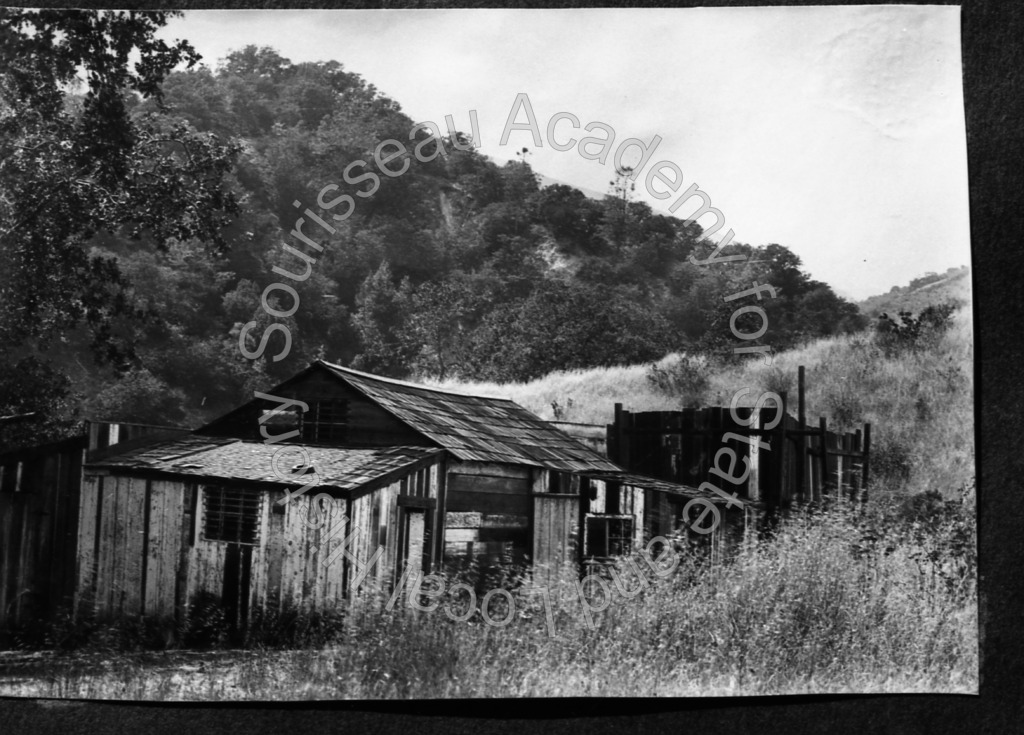

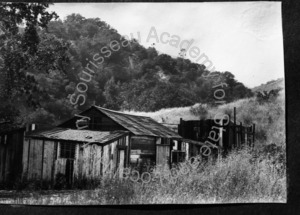

By the onset of the Great Depression, many of Alum Rock Park’s well-used facilities were in need of restoration or renovation while some were unsalvageable and in need of complete removal. Superseded in popularity by the automobile, the less and less used trolley line finally terminated service to and in the park in 1932. The Civil Works Administration, its successor the Works Progress Administration, and other Great Depression-era job-creation agencies oversaw the removal of the old dance pavilion and concessions building as well as much of the derelict railroad infrastructure. Along with the renovation of the Natatorium, further make-work improvements included building new bridges and bathrooms, new picnic areas, a new aviary (now the Ramada picnic enclosure), a penny arcade, a small zoo, the cutting of new hiking and equestrian trails, and the construction of a Spanish-Revival style Lodge, which in 1953 would become home to the Youth Science Institute.

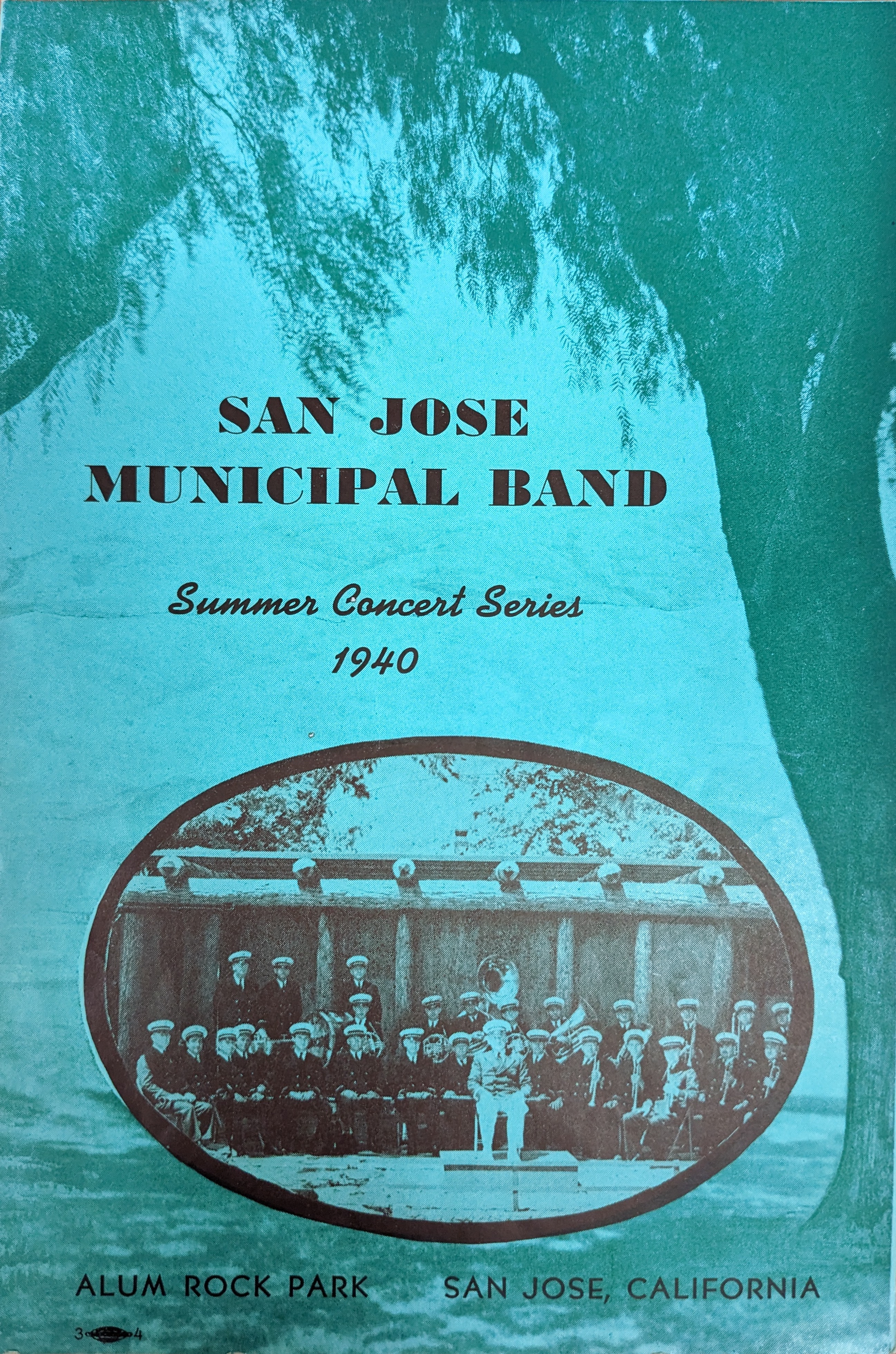

Much of the old Peninsular Railroad railway bed was turned into a hiking trail through the park, known today as the Penitencia Creek Trail. Further up in the foothills, Cherry Flat Dam and Reservoir were constructed on Penitencia Creek to alleviate perennial flooding problems and to provide the park with an abundance of fresh water in the summer. Other improvements in the park, such as a new bandstand, installation of much-needed new lampposts, and additional parking areas were overseen by the newly established Parks and Recreation Department in the 1940s.

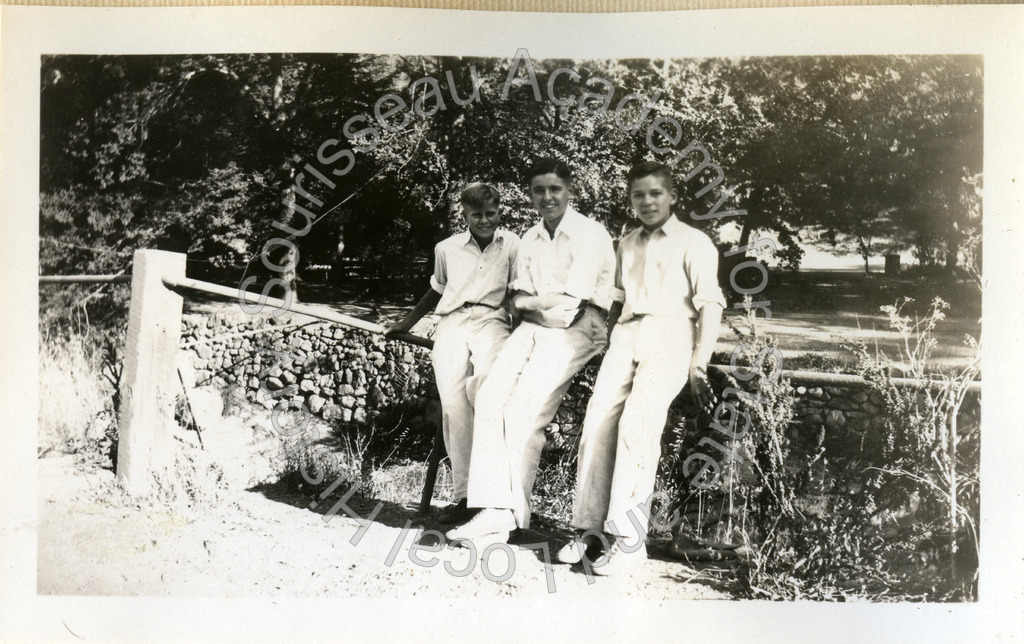

Weekend entertainment such as live bands and dancing in the pavilion, as well as improved picnic, barbeque, and parking areas ensured that the public continued to visit Alum Rock Park even during the upheaval to life caused by World War II. Servicemen who found themselves in the San Francisco Bay Area enjoyed visiting the park and the military often used it for training and overnight camps.

Although the number of visitors to Alum Rock Park decreased during the war years, it was still very popular with the residents of the area throughout the 1940s. The park hosted a summer concert series every Sunday on the park's new bandstand until the mid-1950s. The prosperity boom many Americans enjoyed in the post-war period saw another surge in Alum Rock Park's popularity, primarily focused on the Natatorium and its immediate surroundings, though this was not to last.

Next: Rebuilding the Ecology

Rebuilding the Ecology

The immediate post-war years soon proved to be the last boom period of the park's popularity as people and families began to travel further afield on longer roadtrips that took them out of the immediate San José area. As Alum Rock Park approached its 100th year anniversary, its appeal as a recreation destination had waned due to a number of factors.

Over time, heavy use of the park facilities and surrounding natural areas by large weekend crowds, at their peak numbering over 10,000 people a day, led to the park once again falling into disrepair and decay. The weekend throngs became a thing of the past as people began to favor more exotic and exciting destinations for recreation, and the park gained a reputation for being a seedy and dangerous place by the late 1950s. As decaying attractions were removed, they were not replaced. The zoo animals had been poorly cared for, and the survivors were eventually handed over to Happy Hollow Zoo in the late 1960s. The much-beloved Natatorium closed its doors for good after the 1970 summer season, and five years later the building was razed. Decades of overcrowding, overuse and pollution had taken their toll on the natural environment of the park; the ecosystem of the canyon once hailed as "Little Yosemite" was in real danger of total collapse.

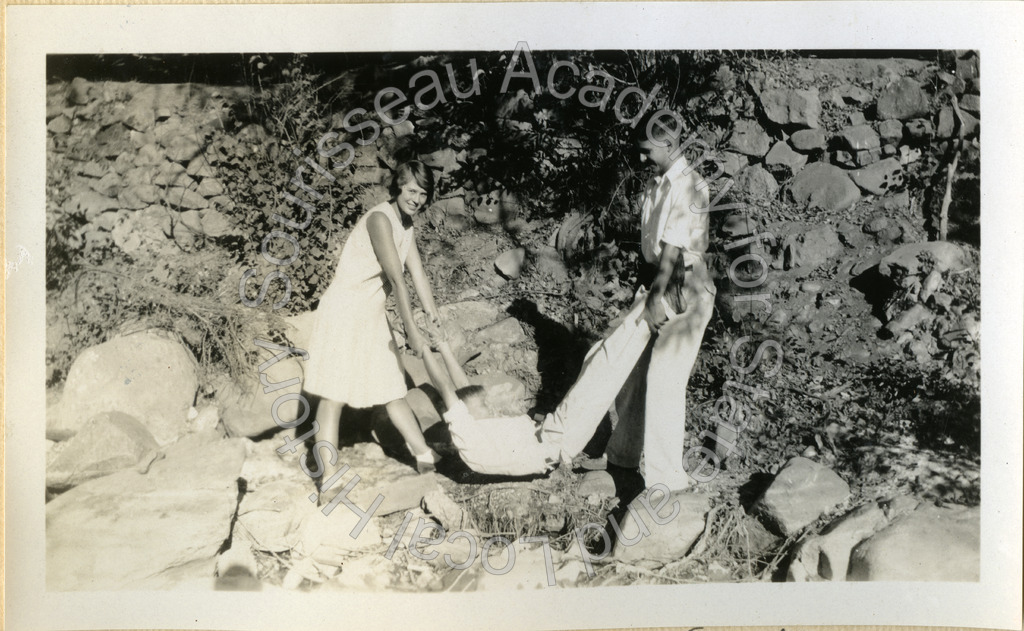

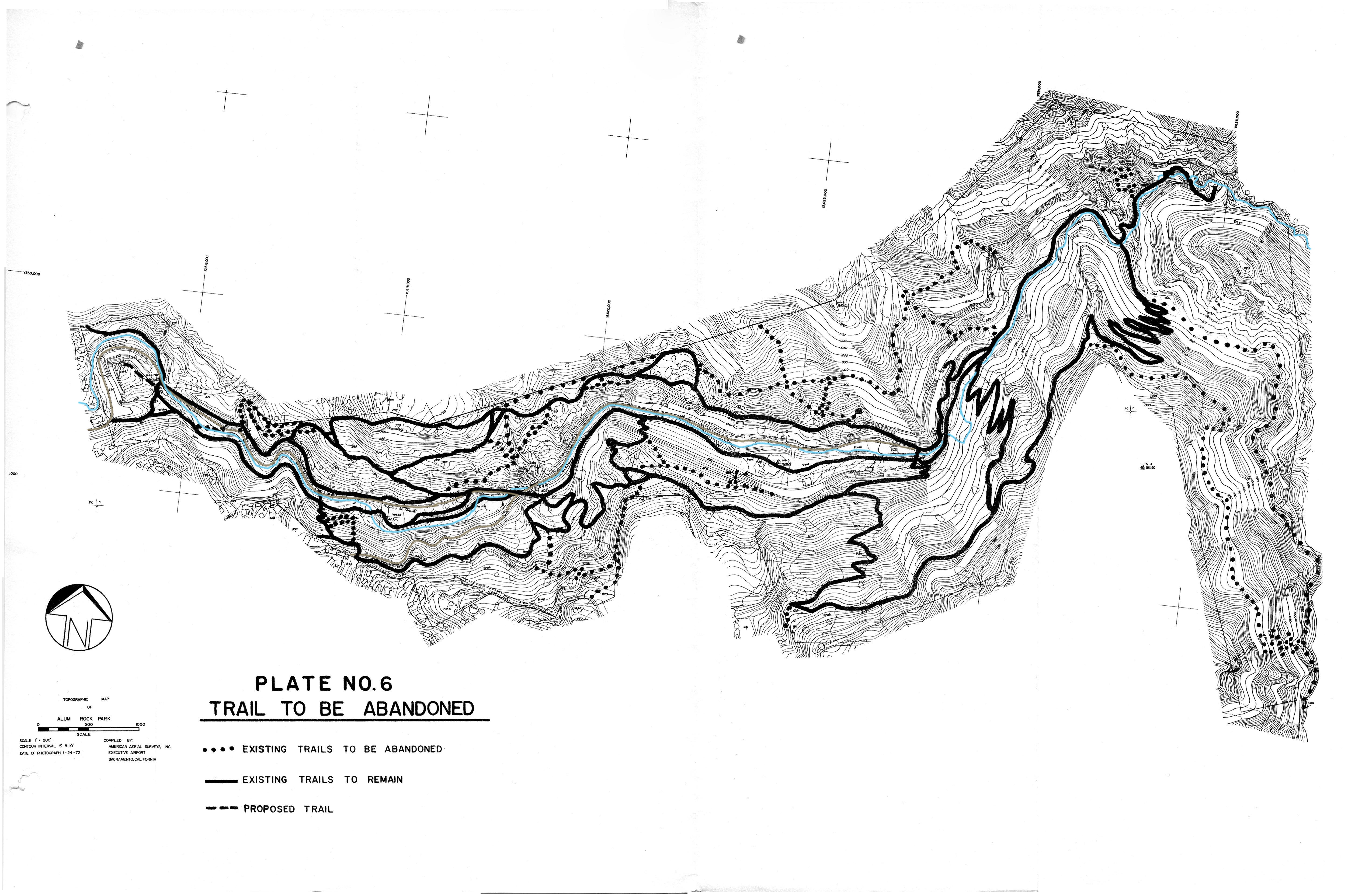

A new awareness of the importance of protecting natural environments for the future, and a better understanding of the impact of ecological health on natural environments, ushered in a new era for Alum Rock Park. Many of the dilapidated structures still in Alum Rock Park were removed, trails to more sensitive and difficult to reach locations were closed, and more attention was paid to restoring the creek, the springs, and their surroundings. Visitors were encouraged to hike, walk, and bike rather than swim in pools. While the lawn, play areas and picnic grounds were maintained, the park encouraged patrons to interact with the flora and fauna in a more sensitive and conscious way. As early as 1953, the nature center now known as the Youth Science Institute began to emphasize the natural history and ecology of the park to visitors.

Although the city of San José continued to encourage visitors to the park, a new emphasis was placed on interacting with the canyon, the creek and their environs in a more environmentally conscious way. Restoration of the canyon and its natural setting became imperative by the late 1960s, and the 1970s saw a major investment by the city into returning the canyon to a more natural state. The cultural and natural history of the park were studied closely during this time, and reports were commissioned in an effort to better understand the full scope of the effects of a century of human activity on the landscape. The fact that Penitencia Creek and its riparian environment are one of the last remaining habitats for a variety of native flora and fauna in the area have made their restoration and conservation paramount.

Next: Celebrating 150 Years

Celebrating 150 Years

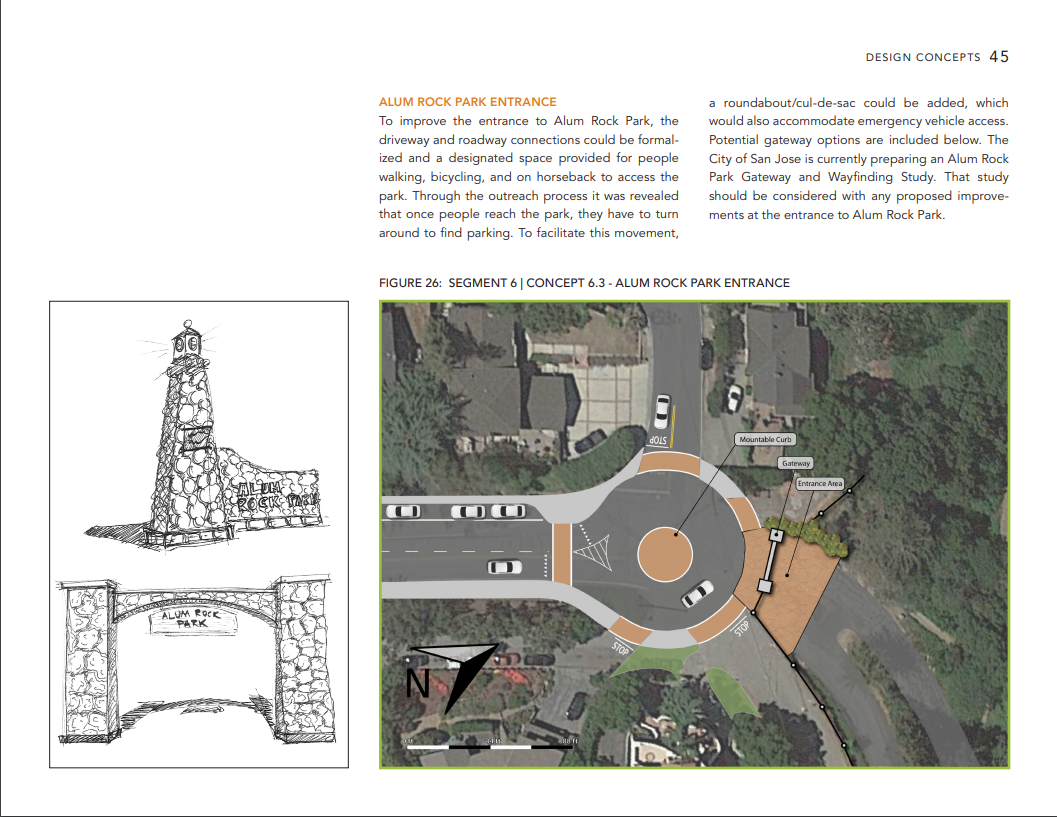

5.jpg)

The focus on conservation and restoration of the park's habitats continued throughout the end of the twentieth century and into the beginning of the twenty-first century. While more popular trails in the park have continued to be maintained over the years, several trails that are more difficult to access or deeper in the park have been closed to hikers since the early 1980s. Flooding and seismic activity during these years also caused some structural damage to several trails, roadways and bridges as well as causing the closure of the original park entrance at Alum Rock Avenue to vehicular traffic. While signs to the park continue to direct visitors to this entrance, it is only open to pedestrian traffic and is no longer the easiest way for most to access the park.

As a result of the extensive restoration efforts undertaken by the city, Alum Rock Park has once again become a popular recreation destination for families, schoolchildren, and summer camps in the twenty first century. It celebrated its 150th anniversary in 2022 with a year of special programming, including guided nature and history tours, an exhibit on park history, and a summer celebration bash. Evidence of the park’s history and use are still visible in its twisting roadways, stone bridges, and well-maintained trails, as well as the mineral springs that are still accessible throughout the park. Visitors often picnic and barbeque in designated areas, and paths to and among the mineral springs remain a popular draw. Hiking, biking, and equestrian trails into the surrounding hills and along Penitencia Creek connect the park to the neighboring Sierra Vista Open Space Preserve and the Bay Area Ridge Trail, making it easy for families and individuals to enjoy the natural beauty of the canyon and the Diablo Range foothills. The focus on preserving the canyon and its environs will ensure that Alum Rock Park continues to be a local destination for another 150 years.

From the very end of 2022 through the first months of 2023, a series of intense storms and torrential rains overcame Penitencia Creek's flood controls, wreaking havoc on the park once more. Trails and roadways were washed out, structures damaged, and a Hollywood-style sign on a bluff overlooking the Penitencia Creek Road entrance collapsed. Closed to the public from December 31, 2022, the San José Department of Parks, Recreation, and Neighborhood Services announced a phased reopening on April 15, 2023, though many trails remain closed due to storm damage.

, Penitencia Creek.jpg)